Christian Mysticism

- Thread starter crossnote

- Start date

-

Christian Chat is a moderated online Christian community allowing Christians around the world to fellowship with each other in real time chat via webcam, voice, and text, with the Christian Chat app. You can also start or participate in a Bible-based discussion here in the Christian Chat Forums, where members can also share with each other their own videos, pictures, or favorite Christian music.

If you are a Christian and need encouragement and fellowship, we're here for you! If you are not a Christian but interested in knowing more about Jesus our Lord, you're also welcome! Want to know what the Bible says, and how you can apply it to your life? Join us!

To make new Christian friends now around the world, click here to join Christian Chat.

Few find the path.

few**plural of few

Adjective

A small number of: "may I ask a few questions?"; "I will recount a few of the stories told me".

Noun

The minority of people; the elect: "a world that increasingly belongs to the few".

Synonyms

adjective.** little - some

noun.** minority

Jesus died a ransom for the MANY., the LOST who could not find the narrow path.

many**plural of man·y

Adjective

A large number of: "many people agreed with her"; "the solution to many of our problems".

Noun

The majority of people: "TV for the many".

Synonyms

adjective.** numerous - much

noun.** multitude

Unless someone tells me that the greek word for "many" is "few", I figured simple definitions mean enough.

Revelation 7:4-9

4*And I heard the number of them which were sealed: and there were sealed an hundred and forty and four thousand of all the tribes of the children of Israel. THE FEW WHO FINDS LIFE

5*Of the tribe of Juda were sealed twelve thousand. Of the tribe of Reuben were sealed twelve thousand. Of the tribe of Gad were sealed twelve thousand.

6*Of the tribe of Aser were sealed twelve thousand. Of the tribe of Nephthalim were sealed twelve thousand. Of the tribe of Manasses were sealed twelve thousand.

7*Of the tribe of Simeon were sealed twelve thousand. Of the tribe of Levi were sealed twelve thousand. Of the tribe of Issachar were sealed twelve thousand.

8*Of the tribe of Zabulon were sealed twelve thousand. Of the tribe of Joseph were sealed twelve thousand. Of the tribe of Benjamin were sealed twelve thousand.

9*After this I beheld, and, lo, a great multitude, which no man could number, of all nations, and kindreds, and people, and tongues, stood before the throne, and before the Lamb, clothed with white robes, and palms in their hands; THE MANY WHO WERE RANSOMED

few**plural of few

Adjective

A small number of: "may I ask a few questions?"; "I will recount a few of the stories told me".

Noun

The minority of people; the elect: "a world that increasingly belongs to the few".

Synonyms

adjective.** little - some

noun.** minority

Jesus died a ransom for the MANY., the LOST who could not find the narrow path.

many**plural of man·y

Adjective

A large number of: "many people agreed with her"; "the solution to many of our problems".

Noun

The majority of people: "TV for the many".

Synonyms

adjective.** numerous - much

noun.** multitude

Unless someone tells me that the greek word for "many" is "few", I figured simple definitions mean enough.

Revelation 7:4-9

4*And I heard the number of them which were sealed: and there were sealed an hundred and forty and four thousand of all the tribes of the children of Israel. THE FEW WHO FINDS LIFE

5*Of the tribe of Juda were sealed twelve thousand. Of the tribe of Reuben were sealed twelve thousand. Of the tribe of Gad were sealed twelve thousand.

6*Of the tribe of Aser were sealed twelve thousand. Of the tribe of Nephthalim were sealed twelve thousand. Of the tribe of Manasses were sealed twelve thousand.

7*Of the tribe of Simeon were sealed twelve thousand. Of the tribe of Levi were sealed twelve thousand. Of the tribe of Issachar were sealed twelve thousand.

8*Of the tribe of Zabulon were sealed twelve thousand. Of the tribe of Joseph were sealed twelve thousand. Of the tribe of Benjamin were sealed twelve thousand.

9*After this I beheld, and, lo, a great multitude, which no man could number, of all nations, and kindreds, and people, and tongues, stood before the throne, and before the Lamb, clothed with white robes, and palms in their hands; THE MANY WHO WERE RANSOMED

Jewish Roots of Eastern Christian Mysticism

Liturgy.pdf

DESERT FATHERS ON MYSTICISM

For who likes to read.

Liturgy.pdf

DESERT FATHERS ON MYSTICISM

For who likes to read.

1

All has been revealed in His word.

If that's not enough, then I don't know what is.

Those who actually had the "mystical" "super natural" experiences, actually longed to look at what has been clearly revealed to us!

1 Peter 1

10 Of this salvation the prophets have inquired and searched carefully, who prophesied of the grace that would come to you, 11 searching what, or what manner of time, the Spirit of Christ who was in them was indicating when He testified beforehand the sufferings of Christ and the glories that would follow. 12 To them it was revealed that, not to themselves, but to us they were ministering the things which now have been reported to you through those who have preached the gospel to you by the Holy Spirit sent from heaven—things which angels desire to look into.

The prophets of old, who had some pretty awesome "experiences" actually SEARCHED hard to find out what has been clearly revealed to us in Jesus and in his word.

Yet so many are so quick to exchange what is clearly revealed for some crazy experience!

How stupid is that?

The prophets of old, who were searching, would shake their heads at us who exchange the clear revelation for some unknown revelation/experience.

If that's not enough, then I don't know what is.

Those who actually had the "mystical" "super natural" experiences, actually longed to look at what has been clearly revealed to us!

1 Peter 1

10 Of this salvation the prophets have inquired and searched carefully, who prophesied of the grace that would come to you, 11 searching what, or what manner of time, the Spirit of Christ who was in them was indicating when He testified beforehand the sufferings of Christ and the glories that would follow. 12 To them it was revealed that, not to themselves, but to us they were ministering the things which now have been reported to you through those who have preached the gospel to you by the Holy Spirit sent from heaven—things which angels desire to look into.

The prophets of old, who had some pretty awesome "experiences" actually SEARCHED hard to find out what has been clearly revealed to us in Jesus and in his word.

Yet so many are so quick to exchange what is clearly revealed for some crazy experience!

How stupid is that?

The prophets of old, who were searching, would shake their heads at us who exchange the clear revelation for some unknown revelation/experience.

We can make spiritual experiences that aren't in the Bible legitimate by pointing out things like car makes that aren't in the Bible? The Book of Mormon isn't in the Bible, but either are solar panels, so the Book of Mormon is legitimate?

Now back on point...What is Christian Mysticism?

I Binged it and found a lot of babble that never really explained it. Then one website made this statement:

Christ is the sole end of Christian mysticism. Whereas all Christians have Christ, call on Christ, and can (or should) know Christ, the goal for the Christian mystic is to become Christ—to become as fully permeated with God as Christ is, thus becoming like him, fully human, and by the grace of God, also fully divine. In Christian teaching this doctrine is known by various names—theosis, divinization, deification, and transforming union. What is Christian mysticism?

If the goal is to become Christ, it's a false religion.

Christ is the sole end of Christian mysticism. Whereas all Christians have Christ, call on Christ, and can (or should) know Christ, the goal for the Christian mystic is to become Christ—to become as fully permeated with God as Christ is, thus becoming like him, fully human, and by the grace of God, also fully divine. In Christian teaching this doctrine is known by various names—theosis, divinization, deification, and transforming union. What is Christian mysticism?

If the goal is to become Christ, it's a false religion.

what is it?

doorway to the occult or God's narrow way?

doorway to the occult or God's narrow way?

I believe your statement with all my heart, soul and mind. Mysticism is nothing more than taking power and authority to oneself, just like Satan did and does.

We must keep in mind also that although some historically very holy to God people have been labeled "mystics," while they never pretended to be anything more or less than faithful to Yahweh, God. Words misused have the habit of mixing the bitter with the batter. This ought not be so, but unhappily, it is.

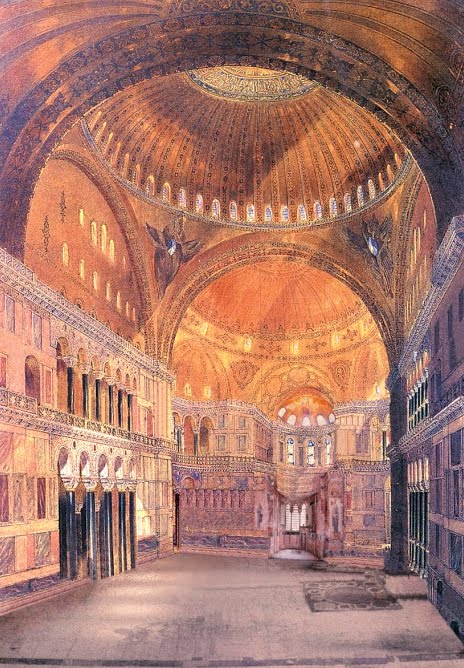

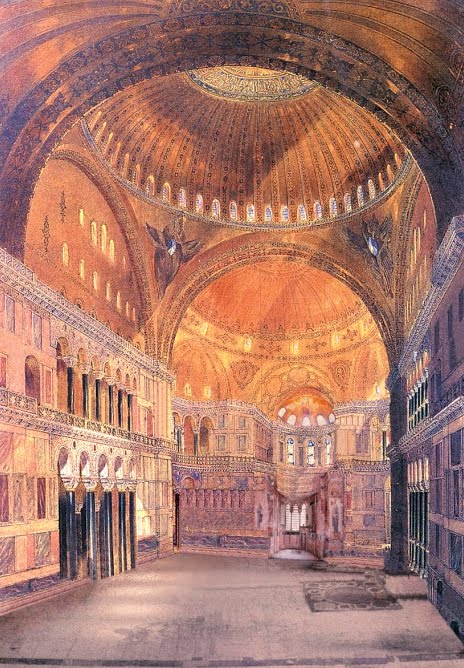

Part I: What Is Orthodox Mysticism?

Mysticism in general and Christian Mysticism as a sub-category are both enormous topics, and the phenomena as a whole is beyond the scope of this thread. Here, our task is to focus more precisely on mysticism as it developed in the Orthodox Christian tradition.

To begin with, Eastern Orthodoxy is defined adequately enough at Wikipedia as follows:

It can also be thought of as the largest manifestation of Eastern Christianity. The eastern and western forms of Christianity were not generally seen to be separate until the East-West Schism of 1054, after which they formally split from each other.

What distinguishes Orthodox mysticism from other forms of mysticism? What follows is a rough overview of some distinctive aspects of this spiritual path, before we go on to look at specifics.

Theosis: The Mystical Transformation

The term theosis is used by Orthodox mystics to describe the highest mystical experience of divine union. It has been translated many different ways in English, including “ingodding” and “divinization,” but I find none of these words fully satisfactory. In the 4th century, Athanasius of Alexandria wrote about Christ that “He became man that we might be made God.” This idea sounds uncomfortably close to pantheism for many Christians, and arguments about what exactly this means have raged through the centuries. We will explore this further in later posts.

Stages of the Spiritual Journey

Both east and western forms of Christian mysticism often distinguish the journey to mystical union with God as unfolding in three stages. The eastern mode tends to follow the scheme of Evagrius of Pontus (346–399) who conceived of the three as: 1) the active life (seeking freedom from passions and purity of heart); 2) the natural contemplation, (seeing God in all things), and 3) Theoria (encountering God through the union of love). Not all orthodox mystics followed this scheme; for Gregory of Nyssa, who we will look at a bit later, the stages were conceived of as “light”, “cloud,” and “darkness,” for example.

The Path of Negation

The Via Negativa or “Negative Way” (also called apophaticism) is the tendency to describe the Divine in terms of what it “isn’t” rather than what it is. Many (but not all) of the Orthodox mystics emphasize the unknowability of God and the splendor of the divine “mystery.” The Orthodox theologians were less analytical than their medieval European counterparts, who tried to express their faith in terms of logic and rational thought. Emptiness, darkness, silence, voidness, and similar “negative” formulations are used more heavily in the Christian east to describe the Divine and the mystical experience. To approach God, one had to empty and still the mind through mystical prayer.

Mystical Prayer

Contemplative prayer is of key importance in the Orthodox mystic’s quest for union with God. The mystic seeks a state known as hesychia, or “inner stillness,” transcending discursive thinking to achieve direct union with the Divine. Many methods of prayer are used in the Orthodox tradition. We will look at one of the most well-know a bit later, the so-called “Jesus prayer.” Constantly repeated thousands of times a day, it starts as a “prayer of the lips,” becomes a “prayer of the mind,” and then finally a “prayer of the heart,” focusing the mystic’s consciousness on the presence of God in a quest for spiritual illumination. It has been compared to the mantras of Hinduism and Buddhism, although important differences exist. Orthodox mystical prayer tends to rely less on complex visualization (as with Catholic discursive prayer or Buddhist visualization, for example), with more emphasis on stillness, silence, and the divine darkness of unknowing.

The Patristic Way

The so-called Early Church Fathers were writers in the first few centuries after Christ who hammered out the philosophical specifics of Christian thought, mystical and otherwise. They are generally respected by Catholics, Protestants, and Orthodox Christians alike, but their writings play a much more prominent role in the Orthodox tradition. The Church Fathers and the so-called Desert Fathers wrote much on mysticism and spirituality, and their writings provide the philosophical and theoretical backbone of Orthodox mysticism.

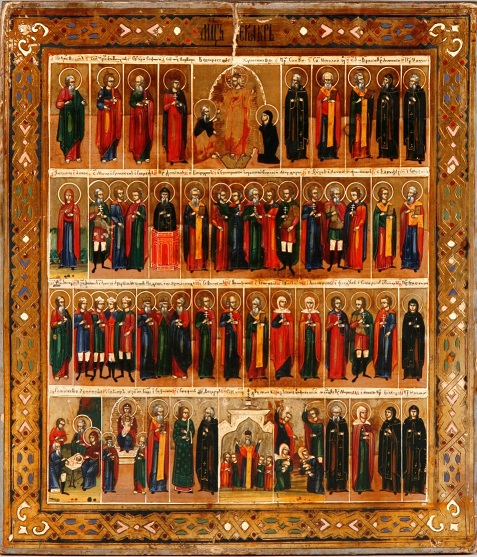

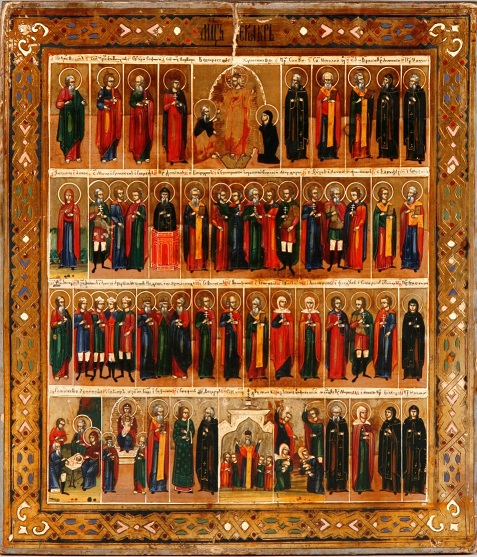

The Icon

The Icon is a special form of religious painting that plays a complex role in Orthodox mysticism. The image is not worshiped, but rather is seen as a kind of “portal” through which the numinous dimension of the Divine can be accessed. An Icon is both a symbolic representation of a divine truth and a visual tool with spiritual and mystical applications.

A Kaleidoscope of Mystical Traditions

We can only scratch the surface here, but the mystical experience has been formulated in a bewildering variety of ways in the Orthodox tradtion. Many local saints, monks, wanderers, and holy men had their own idiosyncratic mystical teachings. Some emphasized asceticism and renunciation of the world, other preached a more active life. Some wrote of the Divine in terms of unknowable darkness, others celebrated the splendor of the light that emanated from God. Austere paths of self-denial were central to some, while others celebrated a mystical love. others c In different times and places, Orthodox mysticism was formulated very differently. This glittering variety makes the study of this type of spirituality all the more interesting.

Mysticism in general and Christian Mysticism as a sub-category are both enormous topics, and the phenomena as a whole is beyond the scope of this thread. Here, our task is to focus more precisely on mysticism as it developed in the Orthodox Christian tradition.

To begin with, Eastern Orthodoxy is defined adequately enough at Wikipedia as follows:

The Orthodox Church, officially called the Orthodox Catholic Church and commonly referred to as the Eastern Orthodox Church is the second largest Christian denomination in the world, with an estimated 300 million adherents, mainly in the countries of Belarus, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Georgia, Greece, Macedonia, Moldova, Montenegro, Romania, Russia, Serbia, and Ukraine, all of which are majority Eastern Orthodox. It is seen by followers to be the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church established by Jesus Christ and his Apostles almost 2,000 years ago.

It can also be thought of as the largest manifestation of Eastern Christianity. The eastern and western forms of Christianity were not generally seen to be separate until the East-West Schism of 1054, after which they formally split from each other.

What distinguishes Orthodox mysticism from other forms of mysticism? What follows is a rough overview of some distinctive aspects of this spiritual path, before we go on to look at specifics.

Theosis: The Mystical Transformation

The term theosis is used by Orthodox mystics to describe the highest mystical experience of divine union. It has been translated many different ways in English, including “ingodding” and “divinization,” but I find none of these words fully satisfactory. In the 4th century, Athanasius of Alexandria wrote about Christ that “He became man that we might be made God.” This idea sounds uncomfortably close to pantheism for many Christians, and arguments about what exactly this means have raged through the centuries. We will explore this further in later posts.

Stages of the Spiritual Journey

Both east and western forms of Christian mysticism often distinguish the journey to mystical union with God as unfolding in three stages. The eastern mode tends to follow the scheme of Evagrius of Pontus (346–399) who conceived of the three as: 1) the active life (seeking freedom from passions and purity of heart); 2) the natural contemplation, (seeing God in all things), and 3) Theoria (encountering God through the union of love). Not all orthodox mystics followed this scheme; for Gregory of Nyssa, who we will look at a bit later, the stages were conceived of as “light”, “cloud,” and “darkness,” for example.

The Path of Negation

The Via Negativa or “Negative Way” (also called apophaticism) is the tendency to describe the Divine in terms of what it “isn’t” rather than what it is. Many (but not all) of the Orthodox mystics emphasize the unknowability of God and the splendor of the divine “mystery.” The Orthodox theologians were less analytical than their medieval European counterparts, who tried to express their faith in terms of logic and rational thought. Emptiness, darkness, silence, voidness, and similar “negative” formulations are used more heavily in the Christian east to describe the Divine and the mystical experience. To approach God, one had to empty and still the mind through mystical prayer.

Mystical Prayer

Contemplative prayer is of key importance in the Orthodox mystic’s quest for union with God. The mystic seeks a state known as hesychia, or “inner stillness,” transcending discursive thinking to achieve direct union with the Divine. Many methods of prayer are used in the Orthodox tradition. We will look at one of the most well-know a bit later, the so-called “Jesus prayer.” Constantly repeated thousands of times a day, it starts as a “prayer of the lips,” becomes a “prayer of the mind,” and then finally a “prayer of the heart,” focusing the mystic’s consciousness on the presence of God in a quest for spiritual illumination. It has been compared to the mantras of Hinduism and Buddhism, although important differences exist. Orthodox mystical prayer tends to rely less on complex visualization (as with Catholic discursive prayer or Buddhist visualization, for example), with more emphasis on stillness, silence, and the divine darkness of unknowing.

The Patristic Way

The so-called Early Church Fathers were writers in the first few centuries after Christ who hammered out the philosophical specifics of Christian thought, mystical and otherwise. They are generally respected by Catholics, Protestants, and Orthodox Christians alike, but their writings play a much more prominent role in the Orthodox tradition. The Church Fathers and the so-called Desert Fathers wrote much on mysticism and spirituality, and their writings provide the philosophical and theoretical backbone of Orthodox mysticism.

The Icon

The Icon is a special form of religious painting that plays a complex role in Orthodox mysticism. The image is not worshiped, but rather is seen as a kind of “portal” through which the numinous dimension of the Divine can be accessed. An Icon is both a symbolic representation of a divine truth and a visual tool with spiritual and mystical applications.

A Kaleidoscope of Mystical Traditions

We can only scratch the surface here, but the mystical experience has been formulated in a bewildering variety of ways in the Orthodox tradtion. Many local saints, monks, wanderers, and holy men had their own idiosyncratic mystical teachings. Some emphasized asceticism and renunciation of the world, other preached a more active life. Some wrote of the Divine in terms of unknowable darkness, others celebrated the splendor of the light that emanated from God. Austere paths of self-denial were central to some, while others celebrated a mystical love. others c In different times and places, Orthodox mysticism was formulated very differently. This glittering variety makes the study of this type of spirituality all the more interesting.