Part II: The Desert Fathers and Early Orthodox Mysticism

The roots of Orthodox mysticism are complex, with numerous imputs. Events in the life of Christ, the sudden conversion of Paul, and certain experiences of the Apostles are usually cited in discussions on earliest forms of Christian mysticism. The Gnostic sects, Jewish mysticism, and Neoplationism had some influence on the course on the development of early Orthodox spirituality. During the historical epoch known as “Late Antiquity,” many different spiritualities and philosophies were interacting and influencing each other, from Egyptian and Hermetic ideas to Chaldean, Persian, and even Indian thought.

The so-called Church Fathers and Desert Fathers are respected by most forms of Christianity, but they have been particularly influential on Orthodox thinkers and mystics. We will look at a few important examples below.

Clement of Alexandria (c. 150 to 215)

Not much is known about Clement’s life. He was head of the so-called Catechetical School in the city of Alexandria. During the time, many different ideas and faiths were swirling together in this dynamic city. He was the first to use the word “mysticism” with reference to Christianity.

Key mystical teachings:

Origen (c. 185 - 254)

Origin was another Aleandrian, and a pupil of Clement’s who succeeded him as the leader of the Catechetical School. He wrote on many subjects and was very influential in both Eastern and Western theology, although he was controversial and many of his ideas have been considered heretical.

Key mystical teachings:

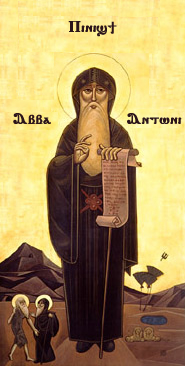

Influenced by the thought of Clement and Origin, as well as the life of Christ himself, increasing numbers of men and women began to withdraw to the desert to live quiet lives of solitude and spiritual struggle. Most of these mystics embraced poverty, prayer, fasting, solitude, and ascetic self-denial as a way to escape the world and turn inward, pursuing divine illumination. Mostly solitary at first, the first Christian monestaries developed out of this tendency to solitude and renunciation.

The most well-known Desert fathers include Anthony the Great (pictured above), Abba Arsenius, Abba Poemen, Abba Macarius of Egypt, Abba Moses the Robber, and Amma Syncletica of Alexandria, Pachomius and Shenouda the Archimandrite. Their sayings have been collected in works such as The Paradise of the Desert Fathers, and cherished by generations of mystical seekers.

Gregory of Nyssa (330-395)

Along with his brother Basil the Great and Gregory of Nazianzus. Gregory of Nyssa is one of the three great “Cappadocian Fathers.” After many years as a solitary monk, Gregory took on a more active role as a bishop and a leading theologian.

Key mystical teachings:

Dionysius the Areopagite (c. 500)

This author is sometimes called “Pseudo-Dionysius” because the name he wrote under was that of an earlier figure in Christian history. His Mystical Theology is perhaps the most influential and towering work of early Christian mysticism, and it had an enormous influence in both the Eastern and Western churches.

Key mystical teachings:

The roots of Orthodox mysticism are complex, with numerous imputs. Events in the life of Christ, the sudden conversion of Paul, and certain experiences of the Apostles are usually cited in discussions on earliest forms of Christian mysticism. The Gnostic sects, Jewish mysticism, and Neoplationism had some influence on the course on the development of early Orthodox spirituality. During the historical epoch known as “Late Antiquity,” many different spiritualities and philosophies were interacting and influencing each other, from Egyptian and Hermetic ideas to Chaldean, Persian, and even Indian thought.

The so-called Church Fathers and Desert Fathers are respected by most forms of Christianity, but they have been particularly influential on Orthodox thinkers and mystics. We will look at a few important examples below.

Clement of Alexandria (c. 150 to 215)

Not much is known about Clement’s life. He was head of the so-called Catechetical School in the city of Alexandria. During the time, many different ideas and faiths were swirling together in this dynamic city. He was the first to use the word “mysticism” with reference to Christianity.

Key mystical teachings:

- Some non-Christian ideas, such as from classical philosophy, are also gifts from God, although subordinate to scripture. Clement tried to Christianize a number of neo-Platonic ideas.

- “True gnosis” is different from the “false gnosis” of the so-called Gnostic Christian sects. True gnosis is not necessary for salvation, but a gift from Christ, a special direct experience of the Divine accessible through spiritual discipline. By achieving a state of “passionlessness,” the mystical seeker attempts to “become like God.”

- The mystical journey has three steps, which can be compared to the three days of Abraham’s journey in Genesis: “the perception of beauties” is followed by “the desire of the good soul,” and finally “the eyes of the understanding [are] opened by the Teacher who rose again the third day.” If God grants the seeker success with the highest contemplation as a special gift, Christ “seals the divine image upon the soul."

- Clement distinguished “contemplation” and “action” on the spiritual journey, using the Mary and Martha story from the Book of Luke as a symbol to explain these two types of spirituality.

Origen (c. 185 - 254)

Origin was another Aleandrian, and a pupil of Clement’s who succeeded him as the leader of the Catechetical School. He wrote on many subjects and was very influential in both Eastern and Western theology, although he was controversial and many of his ideas have been considered heretical.

Key mystical teachings:

- Scripture is full of many rich spiritual meanings, in the form of metaphor and allegory. Scripture should not be read narrowly or as literal truth; rather, it should be contemplated more mystically, to draw out the “secret and hidden things of God” within.

- Self-denial, discipline, ascetic practices, mortification of the flesh, renunciation of sexuality, annihilation of base desire, and the like are roads to mystical experience. Origen was very severe in his asceticism and it is said he castrated himself as a young man in an attempt to combat desire.

- The soul is created in the image of God, and this evidence of special connection between the human mind and God. God can be approached successively, in stages.

- The Song of Songs expresses the mystery of union of the soul and God, and of the Church and God. Origen saw three different levels of meanings: 1) as a simple and passionate wedding poem; 2) as an expression of Christ’s love for Christians, and an expression of the hunger of the soul for the divine Word.

The Desert Fathers

Influenced by the thought of Clement and Origin, as well as the life of Christ himself, increasing numbers of men and women began to withdraw to the desert to live quiet lives of solitude and spiritual struggle. Most of these mystics embraced poverty, prayer, fasting, solitude, and ascetic self-denial as a way to escape the world and turn inward, pursuing divine illumination. Mostly solitary at first, the first Christian monestaries developed out of this tendency to solitude and renunciation.

The most well-known Desert fathers include Anthony the Great (pictured above), Abba Arsenius, Abba Poemen, Abba Macarius of Egypt, Abba Moses the Robber, and Amma Syncletica of Alexandria, Pachomius and Shenouda the Archimandrite. Their sayings have been collected in works such as The Paradise of the Desert Fathers, and cherished by generations of mystical seekers.

Gregory of Nyssa (330-395)

Along with his brother Basil the Great and Gregory of Nazianzus. Gregory of Nyssa is one of the three great “Cappadocian Fathers.” After many years as a solitary monk, Gregory took on a more active role as a bishop and a leading theologian.

Key mystical teachings:

- The mystical life is described in terms of the unending ascent of the soul to God, with successive realizations leading the seeker closer to God’s ultimate mystery. The divine element in every soul is an “inner eye” that can be opened to the vision of the sacred. And yet the more one advances, the greater the mystery, which Gregory describes as the “darkness” or hiddenness of the face of God.

- Gregory praised the solitary spirituality of the desert hermits, and practiced as a monk himself for many years. Ultimately, however, he believes contemplation must manifest as action in the real world. Ideally, the most accomplished mystics should be able to maintain the stillness of desert spirituality inside themselves, while engaging actively with the “real world.”

- For Gregory, spiritual life is a continual progression and a journey without end, rather than an unchanging state of perfection. The progress of a mystic in this world is never completed.

Dionysius the Areopagite (c. 500)

This author is sometimes called “Pseudo-Dionysius” because the name he wrote under was that of an earlier figure in Christian history. His Mystical Theology is perhaps the most influential and towering work of early Christian mysticism, and it had an enormous influence in both the Eastern and Western churches.

Key mystical teachings:

- God cannot be known intellectually, but he can be experienced mystically though spiritual discipline. Dionysius speaks of seeking God with an “eyeless mind.”

- God should be conceived of in terms of what he is not, rather than what he is. It is blasphemous and wrong to use the imperfect images of our mind drawn from this fallen world to envision God, a higher order being altogether. By stripping away false ideas of God, we draw closer to God.

- Dionysius describes the three stages of the soul’s movement toward God as Purification, Illumination, and Union. This is similar to the threefold scheme of earlier mystics, although envisioned differently by Dionysius.

- Dionysius wrote: “Ascending upwards from particular to universal conceptions we strip off all qualities in order that we may attain a naked knowledge of that Unknowing which in all existent things is enwrapped by al objects of knowledge, and that we may begin to see that super-essential Darkness which is hidden by all the light that is in existent things.” He says God “plunges the true initiate into the Darkness of Unknowing [to belong] wholly to Him who is beyond all things and to no one else [and to gain] a knowledge that exceeds understanding.”