God or Guns?

- Thread starter iog

- Start date

-

Christian Chat is a moderated online Christian community allowing Christians around the world to fellowship with each other in real time chat via webcam, voice, and text, with the Christian Chat app. You can also start or participate in a Bible-based discussion here in the Christian Chat Forums, where members can also share with each other their own videos, pictures, or favorite Christian music.

If you are a Christian and need encouragement and fellowship, we're here for you! If you are not a Christian but interested in knowing more about Jesus our Lord, you're also welcome! Want to know what the Bible says, and how you can apply it to your life? Join us!

To make new Christian friends now around the world, click here to join Christian Chat.

Lets read God's constitution and pay attention who is first in his covenant

Exodus 20:1-5,7-8 (KJV)

And God spake all these words, saying, [2] I am the Lord thy God, which have brought thee out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage.

[3] Thou shalt have no other gods before me.

4 Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth:

[5]Thou shalt not bow down thyself to them, nor serve them: for I the Lord thy God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children unto the third and fourth generation of them that hate me;

7] Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain; for the Lord will not hold him guiltless that taketh his name in vain.

8] Remember the sabbath day, to keep it holy.

In God's global laws He is first not the people

Notice there is no weapons, no rights to bear arms

You did not know that did you?

Go learn God's laws first then and only then will you understand US laws

Exodus 20:1-5,7-8 (KJV)

And God spake all these words, saying, [2] I am the Lord thy God, which have brought thee out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage.

[3] Thou shalt have no other gods before me.

4 Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth:

[5]Thou shalt not bow down thyself to them, nor serve them: for I the Lord thy God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children unto the third and fourth generation of them that hate me;

7] Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain; for the Lord will not hold him guiltless that taketh his name in vain.

8] Remember the sabbath day, to keep it holy.

In God's global laws He is first not the people

Notice there is no weapons, no rights to bear arms

You did not know that did you?

Go learn God's laws first then and only then will you understand US laws

Lets read the commandments God setup on Howard love his fellow man

Exodus 20:12-17 (KJV)

Honour thy father and thy mother: that thy days may be long upon the land which the Lord thy God giveth thee. [13] Thou shalt not kill. [14] Thou shalt not commit adultery. [15] Thou shalt not steal. [16] Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour. [17] Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour's house, thou shalt not covet thy neighbour's wife, nor his manservant, nor his maidservant, nor his ox, nor his ass, nor any thing that is thy neighbour's.

Notice not one talks about carrying a weapon

Actually there is one that tells us not to kill

The global laws from the creator Jesus is being ignored

Are these Global laws life or death?

Matthew 19:17 (KJV)

And he said unto him, Why callest thou me good? there is none good but one, that is , God: but if thou wilt enter into life, keep the commandments.

Romans 7:12 (KJV)

Wherefore the law is holy, and the commandment holy, and just, and good.

Romans 7:10 (KJV)

And the commandment, which was ordained to life, I found to be unto death.

Exodus 20:12-17 (KJV)

Honour thy father and thy mother: that thy days may be long upon the land which the Lord thy God giveth thee. [13] Thou shalt not kill. [14] Thou shalt not commit adultery. [15] Thou shalt not steal. [16] Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour. [17] Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour's house, thou shalt not covet thy neighbour's wife, nor his manservant, nor his maidservant, nor his ox, nor his ass, nor any thing that is thy neighbour's.

Notice not one talks about carrying a weapon

Actually there is one that tells us not to kill

The global laws from the creator Jesus is being ignored

Are these Global laws life or death?

Matthew 19:17 (KJV)

And he said unto him, Why callest thou me good? there is none good but one, that is , God: but if thou wilt enter into life, keep the commandments.

Romans 7:12 (KJV)

Wherefore the law is holy, and the commandment holy, and just, and good.

Romans 7:10 (KJV)

And the commandment, which was ordained to life, I found to be unto death.

Guns are a God to you!

You have clearly said it, the right to protection is a "God" to you.

Guns, (or the right to protect the innocent), are not a god to me.

You have clearly said it, the right to protection is a "God" to you.

Guns, (or the right to protect the innocent), are not a god to me.

I have te armour of God this is why your argument won't stand!

Ephesians 6:11-18 (KJV)

Put on the whole armour of God, that ye may be able to stand against the wiles of the devil. [12] For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places . [13] Wherefore take unto you the whole armour of God, that ye may be able to withstand in the evil day, and having done all, to stand. [14] Stand therefore, having your loins girt about with truth, and having on the breastplate of righteousness; [15] And your feet shod with the preparation of the gospel of peace; [16] Above all, taking the shield of faith, wherewith ye shall be able to quench all the fiery darts of the wicked. [17] And take the helmet of salvation, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God: [18] Praying always with all prayer and supplication in the Spirit, and watching thereunto with all perseverance and supplication for all saints;

You should try it!

Your A.R won't work, your NRA can't lobby to The Lord

Your battle is lost before it begins

You law this to heart with your tradition

Mark 7:6-9 (KJV)

He answered and said unto them, Well hath Esaias prophesied of you hypocrites, as it is written, This people honoureth me with their lips, but their heart is far from me. [7] Howbeit in vain do they worship me, teaching for doctrines the commandments of men. [8] For laying aside the commandment of God, ye hold the tradition of men, as the washing of pots and cups: and many other such like things ye do. [9] And he said unto them, Full well ye reject the commandment of God, that ye may keep your own tradition.

Mark 7:6-9 (KJV)

He answered and said unto them, Well hath Esaias prophesied of you hypocrites, as it is written, This people honoureth me with their lips, but their heart is far from me. [7] Howbeit in vain do they worship me, teaching for doctrines the commandments of men. [8] For laying aside the commandment of God, ye hold the tradition of men, as the washing of pots and cups: and many other such like things ye do. [9] And he said unto them, Full well ye reject the commandment of God, that ye may keep your own tradition.

Are you insane?

Just tell me.

Are you mad?

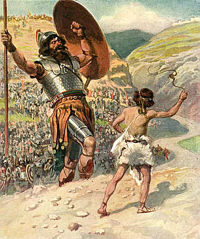

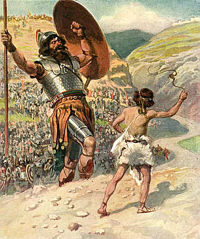

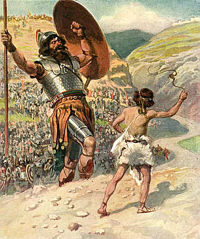

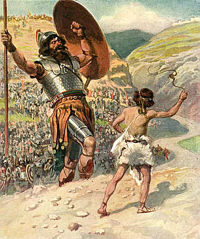

Did David kill?

Why?

You can't answer that because you think Satan does not kill the innocent.

Total corruption of God's Word.

And a spite on all those who died defending the faith in Jesus Christ.

You say they had no faith.

They had faith, you have lies.

When your soul is required of you, where will your lies stand?

Just tell me.

Are you mad?

Did David kill?

Why?

You can't answer that because you think Satan does not kill the innocent.

Total corruption of God's Word.

And a spite on all those who died defending the faith in Jesus Christ.

You say they had no faith.

They had faith, you have lies.

When your soul is required of you, where will your lies stand?

Are you insane?

Just tell me.

Are you mad?

Did David kill?

Why?

You can't answer that because you think Satan does not kill the innocent.

Total corruption of God's Word.

And a spite on all those who died defending the faith in Jesus Christ.

You say they had no faith.

They had faith, you have lies.

When your soul is required of you, where will your lies stand?

Just tell me.

Are you mad?

Did David kill?

Why?

You can't answer that because you think Satan does not kill the innocent.

Total corruption of God's Word.

And a spite on all those who died defending the faith in Jesus Christ.

You say they had no faith.

They had faith, you have lies.

When your soul is required of you, where will your lies stand?

What did God tell you to do ?

Thou shall not kill

The Ten Commandments, Killing, and Murder:

A Detailed Commentary

by Rabbi Dovid Bendory, Rabbinic Director,

Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership.

Copyright 2012 JPFO

This is a detailed commentary, intended to give valuable reference to Jews and Christians who find themselves facing unfounded pacifist dogma.

It is an event that forever changed the course of all human history: the Sinai Revelation. (Exodus 18:1-20:23). Soon after their liberation from Egyptian slavery, the Jewish People encamp at Mt. Sinai where G-d speaks to the entire nation and gives the Ten Commandments.

It is an event that forever changed the course of all human history: the Sinai Revelation. (Exodus 18:1-20:23). Soon after their liberation from Egyptian slavery, the Jewish People encamp at Mt. Sinai where G-d speaks to the entire nation and gives the Ten Commandments.

But one of those ten is among the most commonly mis-translated verses of all of Hebrew Scripture -- and its mis-translation has resulted in deadly mis-interpretation.

Says the Torah (Exodus 20:13): Lo tirtzach!The Hebrew word used has a clear and unequivocal meaning: “Do not murder.”

Unfortunately, this verse is generally mistranslated as “Do not kill.” But the Hebrew could not be more clear, and there is a world of difference between killing and murder.

This is the Sixth Commandment. How many times have you heard “Thou shalt not kill”? This mistranslation is etched upon the hearts and minds of both Jewish and Christian children and adults with pernicious results. Can we possibly estimate the numbers of lives that have been lost by foolish pacifism rather than righteous defense in the face of evil?

Here’s a bit of detail on the “mechanics” of this translation error. If you are ever challenged regarding your corrected understanding, JPFO, once again, gives you the “intellectual ammunition” to hold your ground.

We begin by exploring the English vocabulary and variations on “killing” and “murder”, and we will then explore the nuances of the parallel Hebrew words in order to understand the Biblical text.

In English, there are different ways of stating that “Ploni killed Almoni” depending on the culpability and guilt involved. (The names “Ploni” and “Almoni” are traditionally used in rabbinic commentaries as the Jewish equivalent of “John Doe.” See Ruth 4:1.) Consider the different possible ways of describing the killing:

• First-degree, or pre-meditated murder.

• Second-degree murder; an intentional murder in the spur-of-the-moment, albeit not pre-meditated or planned.

• Voluntary homicide, a form of manslaughter.

• Involuntary homicide, a less culpable form of manslaughter, such as if a driver accidentally hit a jay-walking pedestrian.

Note that “killing” itself need not have a moral context -- a soldier kills in battle, an intended murder victim kills in self-defense, a drug dealer kills his competition, a doctor kills a patient. Whether “killing” caries criminal culpability (the drug dealer), civil culpability (the doctor), or is righteous (the intended murder victim) depends on the context and circumstances.

To understand the Biblical words for “killing” requires first understanding a grammatical point. Hebrew words all contain three-letter roots that provide the core meaning of a word; these three consonants are then vocalized by adding in vowels and attaching prefixes, suffixes, or infixes.

The vowels and attachments are added in specific patterns that determine part of speech, declension, tense, gender, and often specific meaning as well. One such Hebrew root is R-Tz-Ch; it appears in twenty one passages in the Hebrew Scripture. Two of these are in the Ten Commandments (here in Exodus 20:13 and again in Deuteronomy 5) where no context is given. We are twice told that R-Tz-Ch is something we are not to do, but without any context, it is impossible to discern the precise meaning of the term.

However, the root R-Tz-Ch appears multiple times in reference to Cities of Refuge to which an “accidental murderer” can flee. (Numbers 35; Deuteronomy 5, 19; Joshua 20, 21) In each of these passages, the “accidental murderer” has definitely killed someone; the question concerns whether the person killed out of innocence or out of negligence. To use the English terms described above, there has been an involuntary homicide, but whether or not the perpetrator caries culpability or is punishable has not been determined. Such a person is called in Hebrew an “accidental murderer” until s/he stands trial -- and the text explicitly uses the word “accidental” (or “negligent” in conjunction with the root R-Tz-Ch to make this clear. The requirement to clarify that this R-Tz-Ch was accidental demonstrates that without this clarification, R-Tz-Ch is by definition either willful or negligent.

in conjunction with the root R-Tz-Ch to make this clear. The requirement to clarify that this R-Tz-Ch was accidental demonstrates that without this clarification, R-Tz-Ch is by definition either willful or negligent.

Indeed, we find that by far the most common use of R-Tz-Ch is to describe a murderer who kills pre-meditated or with malice. (Deuteronomy 22; Judges 20; 1 Kings 21; 2 Kings 6; Isaiah 1; Jeremiah 7; Ezekiel 21; Hoshea 4, 6; Psalms 42, 62, 94; Proverbs 22; Job 24) When used in this way, the root R-Tz-Ch need not be modified with an adjective or adverb to clarify willful intent; the principle meaning of the word R-Tz-Ch is murder of at least the second degree, possibly first degree. The word implies criminal culpability and guilt, and thus the Sixth Commandment is clearly rendered into English as “do not MURDER.”

As in English -- where we have “murder”, “kill”, “homicide”, and other words -- Hebrew provides other roots to describe “killing.” The other Hebrew words used in connection with taking human life are M-O-T and H-R-G. However, these words were not chosen for the Decalogue. Let’s explore their meanings and how they differ from R-Tz-Ch.

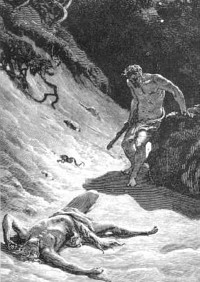

H-R-G is in fact used to describe the first murder in history, Cain’s killing of Abel (Genesis 4:8). As that story makes clear, Cain is responsible for Abel’s death -- but was it willful and intentional?

We are told that “Cain rose up against Abel”, but we are not told if his intention was to kill. Indeed, the Midrash Tanchuma (Bereishit 9) points out that no one had ever died before and that Cain not only did not know how to kill Abel, he didn’t know that killing someone was possible. Cain beat Abel in anger, but in the end was surprised to find that Abel was dead. This is hardly the willful murder of R-Tz-Ch; it is rather H-R-G -- killing, even with criminal culpability, but not even murder of the second degree. Indeed, the word H-R-G is also used to describe the taking of life, whether willful or accidental, in a non-criminal context. It is used by Cain (Genesis 4:14) in his lament, “May whoever finds me take my life.” While H-R-G perhaps describes a willful killing in this usage, it is hardly criminal. For other examples of H-R-G meaning “murder”, see Genesis 20, 27, 37; and especially Exodus 21:14. H-R-G can also refer to righteous killing, such as in self-defense or defense of the innocent; see Exodus 2:14, 4:23, 15:15. But note in these various usages that H-R-G, when it refers to murder, is modified with a word like “intentional” to make it clear that it means “murder” as opposed to “killing.” (e.g., Exodus 21:14) (There are tens of other uses of this word, too numerous to survey in this brief essay.)

Thus, were the Ten Commandments to command us “Don’t H-R-G”, the meaning would be ambivalent -- it could mean murder or killing and would require further descriptive terms like “willful” or “accidental” to make the meaning clear.

The third Hebrew word for death is M-O-T. This word appears in two forms: as an intransitive verb and as a causative verb. In the intransitive, it means “to die” (Genesis 3:3-4); in the causative, it means “to kill” (Genesis 18:25). In the causative form, it is modified (like H-R-G) to indicate whether the killing is a murder (Genesis 37:18) or an appropriate and righteous punishment (Genesis 18:25). In fact, we are told that the murderer (RoTzeaCh) is to be killed (MOT yuMaT) in punishment. (Numbers 35:16-18) The taking of life as a punishment for a capital offense is clearly a morally positive act. Killing is thus obviously permissible -- making it impossible to render the Sixth Commandment as “do not kill.”

The Torah chooses its language very carefully, and indeed, every dot and tittle is parsed to understand the full meaning. G-d chose the root R-Tz-Ch for the Ten Commandments to make it clear and explicit: murder is an evil, heinous crime, a crime that -- like the others in the Ten Commandments -- is destructive of civilization itself. But killing, while a grave action that must be seriously evaluated, is at times a necessary action -- one that is a sanctioned last recourse under prescribed circumstances and one that is occasionally morally appropriate as in the taking of life as penalty for a capital offense.

In fact, killing -- righteous, justified killing -- is the Torah’s Divine punishment for the convicted murderer. This is clear from Numbers 35:16-18 (cited above) as well as Genesis 9:6: “If the blood of one man is spilled by another, his blood shall be spilled.” (In context, this is a clear reference to murder, not merely physical harm.)

Thus while murder -- killing with criminal intent and malice -- is clearly prohibited at all times and in all circumstances, killing itself is not. In a previous commentary, we saw that Moses killed an Egyptian taskmaster who was beating an innocent Hebrew slave. In Hebrew scripture G-d Himself kills in punishment many times -- Noah’s generation, the people of Sodom, and the Egyptian firstborn are a few examples. The courts are commanded to take the life of the convicted murderer as punishment. We are even told that killing to prevent a rape is permissible (Deuteronomy 22:26 as understood in Yoma 82a, Sanhedrin 74a, Pesachim 24b).

While it may be true that Torah and Hebrew Scripture is a vast enough corpus that one can find or read in at least perfunctory support for any idea, there is no question that a proper understanding of Torah Law does not advocate pacifism but rather righteous defense of the innocent. May we never need to rely on such law.

“THOU SHALT NOT MURDER.” the Sixth Commandment

Shalom,

Rabbi Dovid Bendory

Rabbinic Director

Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership

(Jews For The Preservation of Firearms Ownership)

Rabbi Bendory is an NRA Certified Firearms Instructor.

Rabbi Bendory is an NRA Certified Firearms Instructor.

The Rabbi's Archive page.

A Detailed Commentary

by Rabbi Dovid Bendory, Rabbinic Director,

Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership.

Copyright 2012 JPFO

This is a detailed commentary, intended to give valuable reference to Jews and Christians who find themselves facing unfounded pacifist dogma.

But one of those ten is among the most commonly mis-translated verses of all of Hebrew Scripture -- and its mis-translation has resulted in deadly mis-interpretation.

Says the Torah (Exodus 20:13): Lo tirtzach!The Hebrew word used has a clear and unequivocal meaning: “Do not murder.”

Unfortunately, this verse is generally mistranslated as “Do not kill.” But the Hebrew could not be more clear, and there is a world of difference between killing and murder.

This is the Sixth Commandment. How many times have you heard “Thou shalt not kill”? This mistranslation is etched upon the hearts and minds of both Jewish and Christian children and adults with pernicious results. Can we possibly estimate the numbers of lives that have been lost by foolish pacifism rather than righteous defense in the face of evil?

Here’s a bit of detail on the “mechanics” of this translation error. If you are ever challenged regarding your corrected understanding, JPFO, once again, gives you the “intellectual ammunition” to hold your ground.

We begin by exploring the English vocabulary and variations on “killing” and “murder”, and we will then explore the nuances of the parallel Hebrew words in order to understand the Biblical text.

In English, there are different ways of stating that “Ploni killed Almoni” depending on the culpability and guilt involved. (The names “Ploni” and “Almoni” are traditionally used in rabbinic commentaries as the Jewish equivalent of “John Doe.” See Ruth 4:1.) Consider the different possible ways of describing the killing:

• First-degree, or pre-meditated murder.

• Second-degree murder; an intentional murder in the spur-of-the-moment, albeit not pre-meditated or planned.

• Voluntary homicide, a form of manslaughter.

• Involuntary homicide, a less culpable form of manslaughter, such as if a driver accidentally hit a jay-walking pedestrian.

Note that “killing” itself need not have a moral context -- a soldier kills in battle, an intended murder victim kills in self-defense, a drug dealer kills his competition, a doctor kills a patient. Whether “killing” caries criminal culpability (the drug dealer), civil culpability (the doctor), or is righteous (the intended murder victim) depends on the context and circumstances.

To understand the Biblical words for “killing” requires first understanding a grammatical point. Hebrew words all contain three-letter roots that provide the core meaning of a word; these three consonants are then vocalized by adding in vowels and attaching prefixes, suffixes, or infixes.

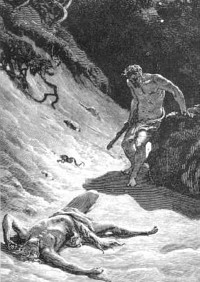

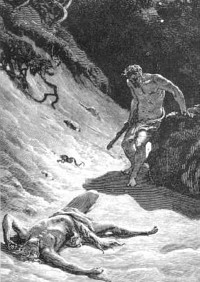

David did not murder Goliath

The vowels and attachments are added in specific patterns that determine part of speech, declension, tense, gender, and often specific meaning as well. One such Hebrew root is R-Tz-Ch; it appears in twenty one passages in the Hebrew Scripture. Two of these are in the Ten Commandments (here in Exodus 20:13 and again in Deuteronomy 5) where no context is given. We are twice told that R-Tz-Ch is something we are not to do, but without any context, it is impossible to discern the precise meaning of the term.

However, the root R-Tz-Ch appears multiple times in reference to Cities of Refuge to which an “accidental murderer” can flee. (Numbers 35; Deuteronomy 5, 19; Joshua 20, 21) In each of these passages, the “accidental murderer” has definitely killed someone; the question concerns whether the person killed out of innocence or out of negligence. To use the English terms described above, there has been an involuntary homicide, but whether or not the perpetrator caries culpability or is punishable has not been determined. Such a person is called in Hebrew an “accidental murderer” until s/he stands trial -- and the text explicitly uses the word “accidental” (or “negligent”

Indeed, we find that by far the most common use of R-Tz-Ch is to describe a murderer who kills pre-meditated or with malice. (Deuteronomy 22; Judges 20; 1 Kings 21; 2 Kings 6; Isaiah 1; Jeremiah 7; Ezekiel 21; Hoshea 4, 6; Psalms 42, 62, 94; Proverbs 22; Job 24) When used in this way, the root R-Tz-Ch need not be modified with an adjective or adverb to clarify willful intent; the principle meaning of the word R-Tz-Ch is murder of at least the second degree, possibly first degree. The word implies criminal culpability and guilt, and thus the Sixth Commandment is clearly rendered into English as “do not MURDER.”

As in English -- where we have “murder”, “kill”, “homicide”, and other words -- Hebrew provides other roots to describe “killing.” The other Hebrew words used in connection with taking human life are M-O-T and H-R-G. However, these words were not chosen for the Decalogue. Let’s explore their meanings and how they differ from R-Tz-Ch.

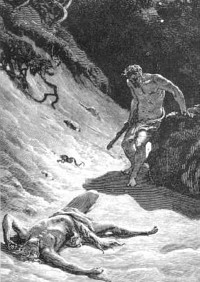

H-R-G is in fact used to describe the first murder in history, Cain’s killing of Abel (Genesis 4:8). As that story makes clear, Cain is responsible for Abel’s death -- but was it willful and intentional?

Did Cain merely kill Abel?

We are told that “Cain rose up against Abel”, but we are not told if his intention was to kill. Indeed, the Midrash Tanchuma (Bereishit 9) points out that no one had ever died before and that Cain not only did not know how to kill Abel, he didn’t know that killing someone was possible. Cain beat Abel in anger, but in the end was surprised to find that Abel was dead. This is hardly the willful murder of R-Tz-Ch; it is rather H-R-G -- killing, even with criminal culpability, but not even murder of the second degree. Indeed, the word H-R-G is also used to describe the taking of life, whether willful or accidental, in a non-criminal context. It is used by Cain (Genesis 4:14) in his lament, “May whoever finds me take my life.” While H-R-G perhaps describes a willful killing in this usage, it is hardly criminal. For other examples of H-R-G meaning “murder”, see Genesis 20, 27, 37; and especially Exodus 21:14. H-R-G can also refer to righteous killing, such as in self-defense or defense of the innocent; see Exodus 2:14, 4:23, 15:15. But note in these various usages that H-R-G, when it refers to murder, is modified with a word like “intentional” to make it clear that it means “murder” as opposed to “killing.” (e.g., Exodus 21:14) (There are tens of other uses of this word, too numerous to survey in this brief essay.)

Thus, were the Ten Commandments to command us “Don’t H-R-G”, the meaning would be ambivalent -- it could mean murder or killing and would require further descriptive terms like “willful” or “accidental” to make the meaning clear.

The third Hebrew word for death is M-O-T. This word appears in two forms: as an intransitive verb and as a causative verb. In the intransitive, it means “to die” (Genesis 3:3-4); in the causative, it means “to kill” (Genesis 18:25). In the causative form, it is modified (like H-R-G) to indicate whether the killing is a murder (Genesis 37:18) or an appropriate and righteous punishment (Genesis 18:25). In fact, we are told that the murderer (RoTzeaCh) is to be killed (MOT yuMaT) in punishment. (Numbers 35:16-18) The taking of life as a punishment for a capital offense is clearly a morally positive act. Killing is thus obviously permissible -- making it impossible to render the Sixth Commandment as “do not kill.”

The Torah chooses its language very carefully, and indeed, every dot and tittle is parsed to understand the full meaning. G-d chose the root R-Tz-Ch for the Ten Commandments to make it clear and explicit: murder is an evil, heinous crime, a crime that -- like the others in the Ten Commandments -- is destructive of civilization itself. But killing, while a grave action that must be seriously evaluated, is at times a necessary action -- one that is a sanctioned last recourse under prescribed circumstances and one that is occasionally morally appropriate as in the taking of life as penalty for a capital offense.

In fact, killing -- righteous, justified killing -- is the Torah’s Divine punishment for the convicted murderer. This is clear from Numbers 35:16-18 (cited above) as well as Genesis 9:6: “If the blood of one man is spilled by another, his blood shall be spilled.” (In context, this is a clear reference to murder, not merely physical harm.)

Thus while murder -- killing with criminal intent and malice -- is clearly prohibited at all times and in all circumstances, killing itself is not. In a previous commentary, we saw that Moses killed an Egyptian taskmaster who was beating an innocent Hebrew slave. In Hebrew scripture G-d Himself kills in punishment many times -- Noah’s generation, the people of Sodom, and the Egyptian firstborn are a few examples. The courts are commanded to take the life of the convicted murderer as punishment. We are even told that killing to prevent a rape is permissible (Deuteronomy 22:26 as understood in Yoma 82a, Sanhedrin 74a, Pesachim 24b).

While it may be true that Torah and Hebrew Scripture is a vast enough corpus that one can find or read in at least perfunctory support for any idea, there is no question that a proper understanding of Torah Law does not advocate pacifism but rather righteous defense of the innocent. May we never need to rely on such law.

“THOU SHALT NOT MURDER.” the Sixth Commandment

Shalom,

Rabbi Dovid Bendory

Rabbinic Director

Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership

(Jews For The Preservation of Firearms Ownership)

The Rabbi's Archive page.

Are you insane?

Just tell me.

Are you mad?

Did David kill?

Why?

You can't answer that because you think Satan does not kill the innocent.

Total corruption of God's Word.

And a spite on all those who died defending the faith in Jesus Christ.

You say they had no faith.

They had faith, you have lies.

When your soul is required of you, where will your lies stand?

Just tell me.

Are you mad?

Did David kill?

Why?

You can't answer that because you think Satan does not kill the innocent.

Total corruption of God's Word.

And a spite on all those who died defending the faith in Jesus Christ.

You say they had no faith.

They had faith, you have lies.

When your soul is required of you, where will your lies stand?

Unless

You think satan is powerful than God

Pay attention

Isaiah 45:6-7 (KJV)

That they may know from the rising of the sun, and from the west, that there is none beside me. I am the Lord , and there is none else. [7] I form the light, and create darkness: I make peace, and create evil: I the Lord do all these things .

Jesus created satan

Jesus created evil

Satan is the evil

Jesus controls satan and the evil

Pay attention

Amos 3:6 (KJV)

Shall a trumpet be blown in the city, and the people not be afraid? shall there be evil in a city, and the Lord hath not done it ?

G

Proverbs 21:1 (KJV)

The king's heart is in the hand of the Lord , as the rivers of water: he turneth it whithersoever he will.

If the king says the guns must go , who put the thought there?

So who is he that is mad at the king or are you mad at The Lord

The king's heart is in the hand of the Lord , as the rivers of water: he turneth it whithersoever he will.

If the king says the guns must go , who put the thought there?

So who is he that is mad at the king or are you mad at The Lord

What idiocy.

It's hard to argue with.

America doesn't have a king.

So by your logic God put it in Hitler's heart to extinguish the Jewish race?

It's hard to argue with.

America doesn't have a king.

So by your logic God put it in Hitler's heart to extinguish the Jewish race?

Why are you here it's obvious this topic is above your understanding

.

The Ten Commandments, Killing, and Murder:

A Detailed Commentary

by Rabbi Dovid Bendory, Rabbinic Director,

Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership.

Copyright 2012 JPFO

This is a detailed commentary, intended to give valuable reference to Jews and Christians who find themselves facing unfounded pacifist dogma.

It is an event that forever changed the course of all human history: the Sinai Revelation. (Exodus 18:1-20:23). Soon after their liberation from Egyptian slavery, the Jewish People encamp at Mt. Sinai where G-d speaks to the entire nation and gives the Ten Commandments.

It is an event that forever changed the course of all human history: the Sinai Revelation. (Exodus 18:1-20:23). Soon after their liberation from Egyptian slavery, the Jewish People encamp at Mt. Sinai where G-d speaks to the entire nation and gives the Ten Commandments.

But one of those ten is among the most commonly mis-translated verses of all of Hebrew Scripture -- and its mis-translation has resulted in deadly mis-interpretation.

Says the Torah (Exodus 20:13): Lo tirtzach!The Hebrew word used has a clear and unequivocal meaning: “Do not murder.”

Unfortunately, this verse is generally mistranslated as “Do not kill.” But the Hebrew could not be more clear, and there is a world of difference between killing and murder.

This is the Sixth Commandment. How many times have you heard “Thou shalt not kill”? This mistranslation is etched upon the hearts and minds of both Jewish and Christian children and adults with pernicious results. Can we possibly estimate the numbers of lives that have been lost by foolish pacifism rather than righteous defense in the face of evil?

Here’s a bit of detail on the “mechanics” of this translation error. If you are ever challenged regarding your corrected understanding, JPFO, once again, gives you the “intellectual ammunition” to hold your ground.

We begin by exploring the English vocabulary and variations on “killing” and “murder”, and we will then explore the nuances of the parallel Hebrew words in order to understand the Biblical text.

In English, there are different ways of stating that “Ploni killed Almoni” depending on the culpability and guilt involved. (The names “Ploni” and “Almoni” are traditionally used in rabbinic commentaries as the Jewish equivalent of “John Doe.” See Ruth 4:1.) Consider the different possible ways of describing the killing:

• First-degree, or pre-meditated murder.

• Second-degree murder; an intentional murder in the spur-of-the-moment, albeit not pre-meditated or planned.

• Voluntary homicide, a form of manslaughter.

• Involuntary homicide, a less culpable form of manslaughter, such as if a driver accidentally hit a jay-walking pedestrian.

Note that “killing” itself need not have a moral context -- a soldier kills in battle, an intended murder victim kills in self-defense, a drug dealer kills his competition, a doctor kills a patient. Whether “killing” caries criminal culpability (the drug dealer), civil culpability (the doctor), or is righteous (the intended murder victim) depends on the context and circumstances.

To understand the Biblical words for “killing” requires first understanding a grammatical point. Hebrew words all contain three-letter roots that provide the core meaning of a word; these three consonants are then vocalized by adding in vowels and attaching prefixes, suffixes, or infixes.

The vowels and attachments are added in specific patterns that determine part of speech, declension, tense, gender, and often specific meaning as well. One such Hebrew root is R-Tz-Ch; it appears in twenty one passages in the Hebrew Scripture. Two of these are in the Ten Commandments (here in Exodus 20:13 and again in Deuteronomy 5) where no context is given. We are twice told that R-Tz-Ch is something we are not to do, but without any context, it is impossible to discern the precise meaning of the term.

However, the root R-Tz-Ch appears multiple times in reference to Cities of Refuge to which an “accidental murderer” can flee. (Numbers 35; Deuteronomy 5, 19; Joshua 20, 21) In each of these passages, the “accidental murderer” has definitely killed someone; the question concerns whether the person killed out of innocence or out of negligence. To use the English terms described above, there has been an involuntary homicide, but whether or not the perpetrator caries culpability or is punishable has not been determined. Such a person is called in Hebrew an “accidental murderer” until s/he stands trial -- and the text explicitly uses the word “accidental” (or “negligent”) in conjunction with the root R-Tz-Ch to make this clear. The requirement to clarify that this R-Tz-Ch was accidental demonstrates that without this clarification, R-Tz-Ch is by definition either willful or negligent.

Indeed, we find that by far the most common use of R-Tz-Ch is to describe a murderer who kills pre-meditated or with malice. (Deuteronomy 22; Judges 20; 1 Kings 21; 2 Kings 6; Isaiah 1; Jeremiah 7; Ezekiel 21; Hoshea 4, 6; Psalms 42, 62, 94; Proverbs 22; Job 24) When used in this way, the root R-Tz-Ch need not be modified with an adjective or adverb to clarify willful intent; the principle meaning of the word R-Tz-Ch is murder of at least the second degree, possibly first degree. The word implies criminal culpability and guilt, and thus the Sixth Commandment is clearly rendered into English as “do not MURDER.”

As in English -- where we have “murder”, “kill”, “homicide”, and other words -- Hebrew provides other roots to describe “killing.” The other Hebrew words used in connection with taking human life are M-O-T and H-R-G. However, these words were not chosen for the Decalogue. Let’s explore their meanings and how they differ from R-Tz-Ch.

H-R-G is in fact used to describe the first murder in history, Cain’s killing of Abel (Genesis 4:8). As that story makes clear, Cain is responsible for Abel’s death -- but was it willful and intentional?

We are told that “Cain rose up against Abel”, but we are not told if his intention was to kill. Indeed, the Midrash Tanchuma (Bereishit 9) points out that no one had ever died before and that Cain not only did not know how to kill Abel, he didn’t know that killing someone was possible. Cain beat Abel in anger, but in the end was surprised to find that Abel was dead. This is hardly the willful murder of R-Tz-Ch; it is rather H-R-G -- killing, even with criminal culpability, but not even murder of the second degree. Indeed, the word H-R-G is also used to describe the taking of life, whether willful or accidental, in a non-criminal context. It is used by Cain (Genesis 4:14) in his lament, “May whoever finds me take my life.” While H-R-G perhaps describes a willful killing in this usage, it is hardly criminal. For other examples of H-R-G meaning “murder”, see Genesis 20, 27, 37; and especially Exodus 21:14. H-R-G can also refer to righteous killing, such as in self-defense or defense of the innocent; see Exodus 2:14, 4:23, 15:15. But note in these various usages that H-R-G, when it refers to murder, is modified with a word like “intentional” to make it clear that it means “murder” as opposed to “killing.” (e.g., Exodus 21:14) (There are tens of other uses of this word, too numerous to survey in this brief essay.)

Thus, were the Ten Commandments to command us “Don’t H-R-G”, the meaning would be ambivalent -- it could mean murder or killing and would require further descriptive terms like “willful” or “accidental” to make the meaning clear.

The third Hebrew word for death is M-O-T. This word appears in two forms: as an intransitive verb and as a causative verb. In the intransitive, it means “to die” (Genesis 3:3-4); in the causative, it means “to kill” (Genesis 18:25). In the causative form, it is modified (like H-R-G) to indicate whether the killing is a murder (Genesis 37:18) or an appropriate and righteous punishment (Genesis 18:25). In fact, we are told that the murderer (RoTzeaCh) is to be killed (MOT yuMaT) in punishment. (Numbers 35:16-18) The taking of life as a punishment for a capital offense is clearly a morally positive act. Killing is thus obviously permissible -- making it impossible to render the Sixth Commandment as “do not kill.”

The Torah chooses its language very carefully, and indeed, every dot and tittle is parsed to understand the full meaning. G-d chose the root R-Tz-Ch for the Ten Commandments to make it clear and explicit: murder is an evil, heinous crime, a crime that -- like the others in the Ten Commandments -- is destructive of civilization itself. But killing, while a grave action that must be seriously evaluated, is at times a necessary action -- one that is a sanctioned last recourse under prescribed circumstances and one that is occasionally morally appropriate as in the taking of life as penalty for a capital offense.

In fact, killing -- righteous, justified killing -- is the Torah’s Divine punishment for the convicted murderer. This is clear from Numbers 35:16-18 (cited above) as well as Genesis 9:6: “If the blood of one man is spilled by another, his blood shall be spilled.” (In context, this is a clear reference to murder, not merely physical harm.)

Thus while murder -- killing with criminal intent and malice -- is clearly prohibited at all times and in all circumstances, killing itself is not. In a previous commentary, we saw that Moses killed an Egyptian taskmaster who was beating an innocent Hebrew slave. In Hebrew scripture G-d Himself kills in punishment many times -- Noah’s generation, the people of Sodom, and the Egyptian firstborn are a few examples. The courts are commanded to take the life of the convicted murderer as punishment. We are even told that killing to prevent a rape is permissible (Deuteronomy 22:26 as understood in Yoma 82a, Sanhedrin 74a, Pesachim 24b).

While it may be true that Torah and Hebrew Scripture is a vast enough corpus that one can find or read in at least perfunctory support for any idea, there is no question that a proper understanding of Torah Law does not advocate pacifism but rather righteous defense of the innocent. May we never need to rely on such law.

“THOU SHALT NOT MURDER.” the Sixth Commandment

Shalom,

Rabbi Dovid Bendory

Rabbinic Director

Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership

(Jews For The Preservation of Firearms Ownership)

Rabbi Bendory is an NRA Certified Firearms Instructor.

Rabbi Bendory is an NRA Certified Firearms Instructor.

The Rabbi's Archive page.

A Detailed Commentary

by Rabbi Dovid Bendory, Rabbinic Director,

Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership.

Copyright 2012 JPFO

This is a detailed commentary, intended to give valuable reference to Jews and Christians who find themselves facing unfounded pacifist dogma.

But one of those ten is among the most commonly mis-translated verses of all of Hebrew Scripture -- and its mis-translation has resulted in deadly mis-interpretation.

Says the Torah (Exodus 20:13): Lo tirtzach!The Hebrew word used has a clear and unequivocal meaning: “Do not murder.”

Unfortunately, this verse is generally mistranslated as “Do not kill.” But the Hebrew could not be more clear, and there is a world of difference between killing and murder.

This is the Sixth Commandment. How many times have you heard “Thou shalt not kill”? This mistranslation is etched upon the hearts and minds of both Jewish and Christian children and adults with pernicious results. Can we possibly estimate the numbers of lives that have been lost by foolish pacifism rather than righteous defense in the face of evil?

Here’s a bit of detail on the “mechanics” of this translation error. If you are ever challenged regarding your corrected understanding, JPFO, once again, gives you the “intellectual ammunition” to hold your ground.

We begin by exploring the English vocabulary and variations on “killing” and “murder”, and we will then explore the nuances of the parallel Hebrew words in order to understand the Biblical text.

In English, there are different ways of stating that “Ploni killed Almoni” depending on the culpability and guilt involved. (The names “Ploni” and “Almoni” are traditionally used in rabbinic commentaries as the Jewish equivalent of “John Doe.” See Ruth 4:1.) Consider the different possible ways of describing the killing:

• First-degree, or pre-meditated murder.

• Second-degree murder; an intentional murder in the spur-of-the-moment, albeit not pre-meditated or planned.

• Voluntary homicide, a form of manslaughter.

• Involuntary homicide, a less culpable form of manslaughter, such as if a driver accidentally hit a jay-walking pedestrian.

Note that “killing” itself need not have a moral context -- a soldier kills in battle, an intended murder victim kills in self-defense, a drug dealer kills his competition, a doctor kills a patient. Whether “killing” caries criminal culpability (the drug dealer), civil culpability (the doctor), or is righteous (the intended murder victim) depends on the context and circumstances.

To understand the Biblical words for “killing” requires first understanding a grammatical point. Hebrew words all contain three-letter roots that provide the core meaning of a word; these three consonants are then vocalized by adding in vowels and attaching prefixes, suffixes, or infixes.

David did not murder Goliath

The vowels and attachments are added in specific patterns that determine part of speech, declension, tense, gender, and often specific meaning as well. One such Hebrew root is R-Tz-Ch; it appears in twenty one passages in the Hebrew Scripture. Two of these are in the Ten Commandments (here in Exodus 20:13 and again in Deuteronomy 5) where no context is given. We are twice told that R-Tz-Ch is something we are not to do, but without any context, it is impossible to discern the precise meaning of the term.

However, the root R-Tz-Ch appears multiple times in reference to Cities of Refuge to which an “accidental murderer” can flee. (Numbers 35; Deuteronomy 5, 19; Joshua 20, 21) In each of these passages, the “accidental murderer” has definitely killed someone; the question concerns whether the person killed out of innocence or out of negligence. To use the English terms described above, there has been an involuntary homicide, but whether or not the perpetrator caries culpability or is punishable has not been determined. Such a person is called in Hebrew an “accidental murderer” until s/he stands trial -- and the text explicitly uses the word “accidental” (or “negligent”) in conjunction with the root R-Tz-Ch to make this clear. The requirement to clarify that this R-Tz-Ch was accidental demonstrates that without this clarification, R-Tz-Ch is by definition either willful or negligent.

Indeed, we find that by far the most common use of R-Tz-Ch is to describe a murderer who kills pre-meditated or with malice. (Deuteronomy 22; Judges 20; 1 Kings 21; 2 Kings 6; Isaiah 1; Jeremiah 7; Ezekiel 21; Hoshea 4, 6; Psalms 42, 62, 94; Proverbs 22; Job 24) When used in this way, the root R-Tz-Ch need not be modified with an adjective or adverb to clarify willful intent; the principle meaning of the word R-Tz-Ch is murder of at least the second degree, possibly first degree. The word implies criminal culpability and guilt, and thus the Sixth Commandment is clearly rendered into English as “do not MURDER.”

As in English -- where we have “murder”, “kill”, “homicide”, and other words -- Hebrew provides other roots to describe “killing.” The other Hebrew words used in connection with taking human life are M-O-T and H-R-G. However, these words were not chosen for the Decalogue. Let’s explore their meanings and how they differ from R-Tz-Ch.

H-R-G is in fact used to describe the first murder in history, Cain’s killing of Abel (Genesis 4:8). As that story makes clear, Cain is responsible for Abel’s death -- but was it willful and intentional?

Did Cain merely kill Abel?

We are told that “Cain rose up against Abel”, but we are not told if his intention was to kill. Indeed, the Midrash Tanchuma (Bereishit 9) points out that no one had ever died before and that Cain not only did not know how to kill Abel, he didn’t know that killing someone was possible. Cain beat Abel in anger, but in the end was surprised to find that Abel was dead. This is hardly the willful murder of R-Tz-Ch; it is rather H-R-G -- killing, even with criminal culpability, but not even murder of the second degree. Indeed, the word H-R-G is also used to describe the taking of life, whether willful or accidental, in a non-criminal context. It is used by Cain (Genesis 4:14) in his lament, “May whoever finds me take my life.” While H-R-G perhaps describes a willful killing in this usage, it is hardly criminal. For other examples of H-R-G meaning “murder”, see Genesis 20, 27, 37; and especially Exodus 21:14. H-R-G can also refer to righteous killing, such as in self-defense or defense of the innocent; see Exodus 2:14, 4:23, 15:15. But note in these various usages that H-R-G, when it refers to murder, is modified with a word like “intentional” to make it clear that it means “murder” as opposed to “killing.” (e.g., Exodus 21:14) (There are tens of other uses of this word, too numerous to survey in this brief essay.)

Thus, were the Ten Commandments to command us “Don’t H-R-G”, the meaning would be ambivalent -- it could mean murder or killing and would require further descriptive terms like “willful” or “accidental” to make the meaning clear.

The third Hebrew word for death is M-O-T. This word appears in two forms: as an intransitive verb and as a causative verb. In the intransitive, it means “to die” (Genesis 3:3-4); in the causative, it means “to kill” (Genesis 18:25). In the causative form, it is modified (like H-R-G) to indicate whether the killing is a murder (Genesis 37:18) or an appropriate and righteous punishment (Genesis 18:25). In fact, we are told that the murderer (RoTzeaCh) is to be killed (MOT yuMaT) in punishment. (Numbers 35:16-18) The taking of life as a punishment for a capital offense is clearly a morally positive act. Killing is thus obviously permissible -- making it impossible to render the Sixth Commandment as “do not kill.”

The Torah chooses its language very carefully, and indeed, every dot and tittle is parsed to understand the full meaning. G-d chose the root R-Tz-Ch for the Ten Commandments to make it clear and explicit: murder is an evil, heinous crime, a crime that -- like the others in the Ten Commandments -- is destructive of civilization itself. But killing, while a grave action that must be seriously evaluated, is at times a necessary action -- one that is a sanctioned last recourse under prescribed circumstances and one that is occasionally morally appropriate as in the taking of life as penalty for a capital offense.

In fact, killing -- righteous, justified killing -- is the Torah’s Divine punishment for the convicted murderer. This is clear from Numbers 35:16-18 (cited above) as well as Genesis 9:6: “If the blood of one man is spilled by another, his blood shall be spilled.” (In context, this is a clear reference to murder, not merely physical harm.)

Thus while murder -- killing with criminal intent and malice -- is clearly prohibited at all times and in all circumstances, killing itself is not. In a previous commentary, we saw that Moses killed an Egyptian taskmaster who was beating an innocent Hebrew slave. In Hebrew scripture G-d Himself kills in punishment many times -- Noah’s generation, the people of Sodom, and the Egyptian firstborn are a few examples. The courts are commanded to take the life of the convicted murderer as punishment. We are even told that killing to prevent a rape is permissible (Deuteronomy 22:26 as understood in Yoma 82a, Sanhedrin 74a, Pesachim 24b).

While it may be true that Torah and Hebrew Scripture is a vast enough corpus that one can find or read in at least perfunctory support for any idea, there is no question that a proper understanding of Torah Law does not advocate pacifism but rather righteous defense of the innocent. May we never need to rely on such law.

“THOU SHALT NOT MURDER.” the Sixth Commandment

Shalom,

Rabbi Dovid Bendory

Rabbinic Director

Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership

(Jews For The Preservation of Firearms Ownership)

The Rabbi's Archive page.

Satan can't do nothing without The Lord's permission

Unless

You think satan is powerful than God

Pay attention

Isaiah 45:6-7 (KJV)

That they may know from the rising of the sun, and from the west, that there is none beside me. I am the Lord , and there is none else. [7] I form the light, and create darkness: I make peace, and create evil: I the Lord do all these things .

Jesus created satan

Jesus created evil

Satan is the evil

Jesus controls satan and the evil

Pay attention

Amos 3:6 (KJV)

Shall a trumpet be blown in the city, and the people not be afraid? shall there be evil in a city, and the Lord hath not done it ?

Unless

You think satan is powerful than God

Pay attention

Isaiah 45:6-7 (KJV)

That they may know from the rising of the sun, and from the west, that there is none beside me. I am the Lord , and there is none else. [7] I form the light, and create darkness: I make peace, and create evil: I the Lord do all these things .

Jesus created satan

Jesus created evil

Satan is the evil

Jesus controls satan and the evil

Pay attention

Amos 3:6 (KJV)

Shall a trumpet be blown in the city, and the people not be afraid? shall there be evil in a city, and the Lord hath not done it ?

Find out what the hebrew word means before you make a claim.

Amos 3:6? Another verse addressing a specific happening taken out of context.

Honestly 'iog', your lack of biblical understanding defeats your purposes here.

Don't forget they were justified in their minds because they were killing heathens in the name of religious freedom. ( How does that work?)

The British believed in Jesus

The RCC believed in Jesus

The founding fathers believed in Jesus

How does that work?

My Jesus is better that your Jesus?

If the king says the guns must stay , who put the thought there?

A perfectly valid question, based on your post quoted above - which you seem to want to avoid answering...

...by using an insult to shift the focus.

.

A perfectly valid question, based on your post quoted above - which you seem to want to avoid answering...

...by using an insult to shift the focus.

.

The God who set the king up put the thought in that kings head and the guns must stay

Proverbs 21:1 (KJV)

The king's heart is in the hand of the Lord , as the rivers of water: he turneth it whithersoever he will.

His mind is in God's hand

Exodus 7:3-4,13 (KJV)

And I will harden Pharaoh's heart, and multiply my signs and my wonders in the land of Egypt. [4] But Pharaoh shall not hearken unto you, that I may lay my hand upon Egypt, and bring forth mine armies, and my people the children of Israel, out of the land of Egypt by great judgments. [13] And he hardened Pharaoh's heart, that he hearkened not unto them; as the Lord had said.