[h=1]Dragons in History[/h]

“The dragons of legend are strangely like actual creatures that have lived in the past. They are much like the great reptiles which inhabited the earth long before man is supposed to have appeared on earth. Dragons were generally evil and destructive. Every country had them in its mythology.” (Knox, Wilson, “Dragon,” The World Book Encyclopedia, vol. 5, 1973, p. 265.) The article on dragons in the Encyclopaedia Britannica (1949 edition) noted that dinosaurs were “astonishingly dragonlike,” even though its author assumed that those ancients who believed in dragons did so “without the slightest knowledge” of dinosaurs. The truth is that the fathers of modern paleontology used the terms “dinosaur” and “dragon” interchangeably for quite some time.

“The dragons of legend are strangely like actual creatures that have lived in the past. They are much like the great reptiles which inhabited the earth long before man is supposed to have appeared on earth. Dragons were generally evil and destructive. Every country had them in its mythology.” (Knox, Wilson, “Dragon,” The World Book Encyclopedia, vol. 5, 1973, p. 265.) The article on dragons in the Encyclopaedia Britannica (1949 edition) noted that dinosaurs were “astonishingly dragonlike,” even though its author assumed that those ancients who believed in dragons did so “without the slightest knowledge” of dinosaurs. The truth is that the fathers of modern paleontology used the terms “dinosaur” and “dragon” interchangeably for quite some time.

Stories of dragons have been handed down for generations in many civilizations. No doubt many of these stories have been exaggerated through the years. But that does not mean they had no original basis in fact. Even some living lizards look like dragons and it is easy to see how a larger variety of such an animal could frighten a community. Have you ever seen an old dinosaur film where they used an iguana in a miniature town set to create the illusion of a great dragon?

Stories of dragons have been handed down for generations in many civilizations. No doubt many of these stories have been exaggerated through the years. But that does not mean they had no original basis in fact. Even some living lizards look like dragons and it is easy to see how a larger variety of such an animal could frighten a community. Have you ever seen an old dinosaur film where they used an iguana in a miniature town set to create the illusion of a great dragon?

In 2004 a fascinating dinosaur skull was donated to the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis by three Sioux City, Iowa, residents who found it during a trip to the Hell Creek Formation in South Dakota. The trio are still excavating the site, looking for more of the dinosaur’s bones. Because of its dragon-like head, horns and teeth, the new species was dubbed Dracorex hogwartsia. This name honors the Harry Potter fictional works, which features the Hogwarts School and recently popularized dragons. The dinosaur’s skull mixes spiky horns, bumps and a long muzzle. But unlike other members of the pachycephalosaur family, which have domed foreheads, this one is flat-headed. Consider some of the ancient stories of dragons, some fictional and some that might be authentic history of dinosaurs.

In 2004 a fascinating dinosaur skull was donated to the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis by three Sioux City, Iowa, residents who found it during a trip to the Hell Creek Formation in South Dakota. The trio are still excavating the site, looking for more of the dinosaur’s bones. Because of its dragon-like head, horns and teeth, the new species was dubbed Dracorex hogwartsia. This name honors the Harry Potter fictional works, which features the Hogwarts School and recently popularized dragons. The dinosaur’s skull mixes spiky horns, bumps and a long muzzle. But unlike other members of the pachycephalosaur family, which have domed foreheads, this one is flat-headed. Consider some of the ancient stories of dragons, some fictional and some that might be authentic history of dinosaurs.

Written about 2,000 B.C. the famous Epic of Gilgamesh records the slaying of the monster Humbaba in Mesopotamia. Humbaba was the terrifying guardian of the Cedar Forest of Amanus. The powerful Mesopotamian god Enlil placed Humbaba there to kill any human that dared disturb its peace. Humbaba was a giant creature, terrifying to look at. Sometimes he is pictured as a large, humanoid shape covered with scale plates. His powerful legs were like that of a lion, but with the talons of a vulture. His head had bull’s horns and his tail was like a serpent. Alternatively, some sources give Humbaba the form of a dragon that could breathe fire. (Drawing to the left by Fafnirx.)

Written about 2,000 B.C. the famous Epic of Gilgamesh records the slaying of the monster Humbaba in Mesopotamia. Humbaba was the terrifying guardian of the Cedar Forest of Amanus. The powerful Mesopotamian god Enlil placed Humbaba there to kill any human that dared disturb its peace. Humbaba was a giant creature, terrifying to look at. Sometimes he is pictured as a large, humanoid shape covered with scale plates. His powerful legs were like that of a lion, but with the talons of a vulture. His head had bull’s horns and his tail was like a serpent. Alternatively, some sources give Humbaba the form of a dragon that could breathe fire. (Drawing to the left by Fafnirx.)

Daniel was said to kill a dragon in the apocryphal chapters of the Bible. King Cyrus challenged Daniel’s refusal to worship the idol Bel. Daniel revealed to the king a conspiracy on the part of the priests to eat the food offered to Bel, making the god seem real. Not only were the deceptive priests executed, but Daniel was allowed to destroy their idol and a dragon that was being worshipped. In the brief narrative of the dragon (14:23-30), Daniel killed the dragon by baking pitch, fat, and hair to make cakes that cause the dragon to burst open upon consumption. In the Hebrew Midrash version, other ingredients serve the purpose of destroying the dragon.

After Alexander the Great invaded India he brought back reports of seeing a great hissing dragon living in a cave. Later Greek rulers supposedly brought dragons alive from Ethiopia. (Gould, Charles, Mythical Monsters, W.H. Allen & Co., London, 1886, pp. 382-383.) Microsoft Encarta Encyclopedia (“Dinosaur” entry) explains that the historical references to dinosaur bones may extend as far back as the 5th century BC. In fact, some scholars think that the Greek historian Herodotus was referring to fossilized dinosaur skeletons and eggs when he described griffins guarding nests in central Asia. “Dragon bones” mentioned in a 3rd century AD text from China are thought to refer to bones of dinosaurs.

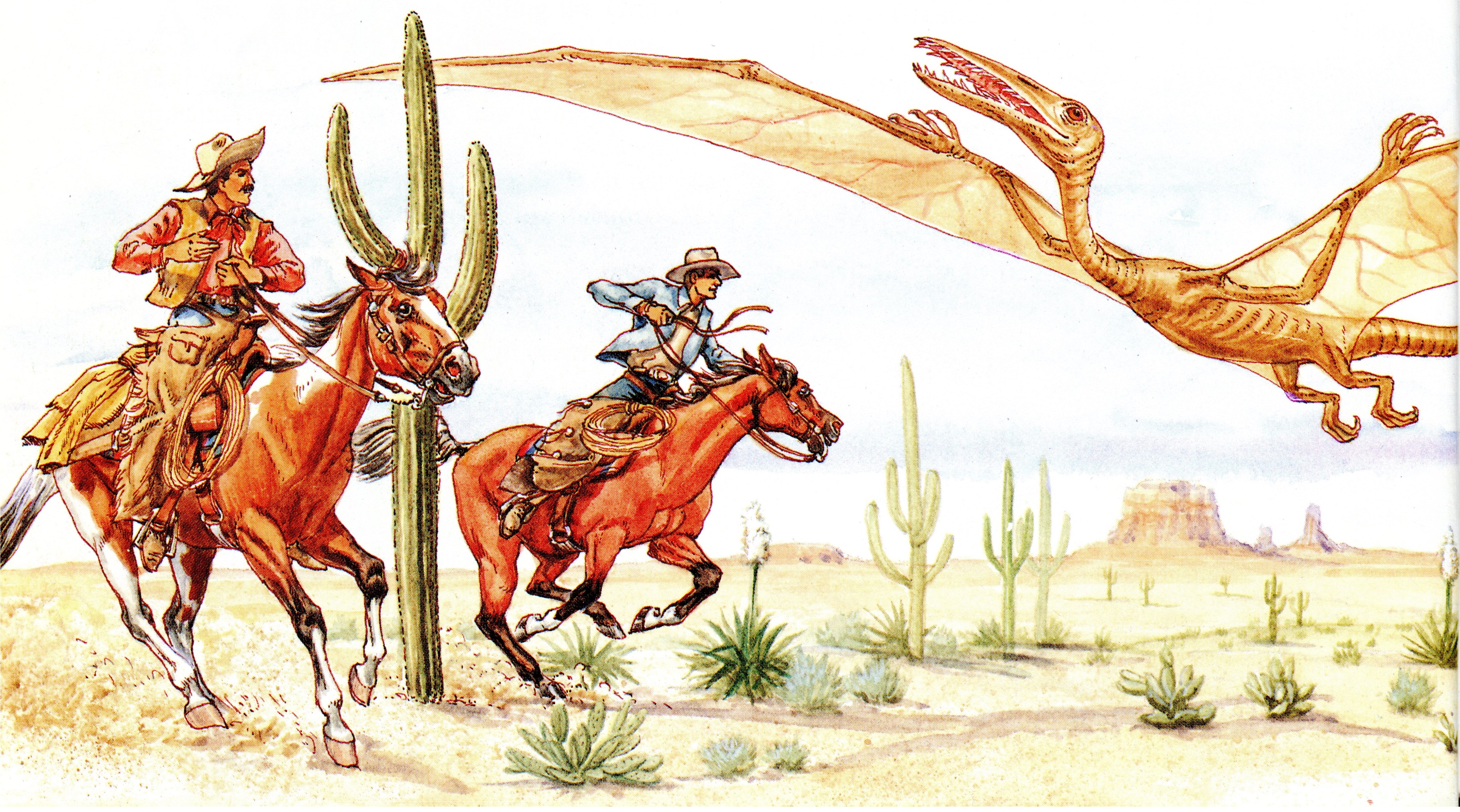

Ancient explorers and historians, like Josephus, told of small flying reptiles in ancient Egypt and Arabia and described their predators, the ibis, stopping their invasion into Egypt. (Epstei+n, Perle S., Monsters: Their Histories, Homes, and Habits, 1973, p.43.) A third century historian Gaius Solinus, discussed the Arabian flying serpents, and stated that “the poison is so quick that death follows before pain can be felt.” (Cobbin, Ingram, Condensed Commentary and Family Exposition on the Whole Bible, 1837, p. 171.) The well-respected Greek researcher Herodotus wrote: “There is a place in Arabia, situated very near the city of Buto, to which I went, on hearing of some winged serpents; and when I arrived there, I saw bones and spines of serpents, in such quantities as it would be impossible to describe. The form of the serpent is like that of the water-snake; but he has wings without feathers, and as like as possible to the wings of a bat.” (Herodotus, Historiae, tr. Henry Clay, 1850, pp. 75-76.) Herodotus has been called “the Father of History” because he was the first historian we know who collected his materials systematically and then tested them for accuracy. John Goertzen noted the Egyptian representation of tail vanes with flying reptiles and concluded that they must have observed pterosaurs or they would not have known to sketch this leaf-shaped tail. He also matched a flying reptile, observed in Egypt and sketched by the outstanding Renaissance scientist Pierre Belon, with the Dimorphodon genus of pterosaur. (Goertzen, J.C., “Shadows of Rhamphorhynchoid Pterosaurs in Ancient Egypt and Nubia,” Cryptozoology, Vol 13, 1998.)

Charles Gould cites the historian Gesner as saying that, “In 1543, a kind of dragon appeared near Styria, within the confines of Germany, which had feet like lizards, and wings after the fashion of a bat, with an incurable bite… He refers to a description by Scaliger (Scaliger, lib. III. Miscellaneous cap. i, “Winged Serpents,” p. 182.) of a species of serpent four feet long, and as thick as a man’s arm, with cartilaginous wings pendent from the sides. He also mentions Brodeus, of a winged dragon which was brought to Francis, the invincible King of the Gauls, by a countryman who had killed it with a mattock near Sanctones, and which was stated to have been seen by many men of approved reputation, who though it had migrated from transmarine regions by the assistance of the wind. Cardan (De Natura Rerum, lib VII, cap. 29.) states that whilst he resided in Paris he saw five winged dragons in the WilliamMuseum; these were biped, and possessed of wings so slender that it was hardly possible that they could fly with them. Cardan doubted their having been fabricated, since they had been sent in vessels at different times, and yet all presented the same

remarkable form. Bellonius states that he had seen whole carcases [sic] of winged dragons, carefully prepared, which he considered to be of the same kind as those which fly out of Arabia into Egypt; they were thick about the belly, had two feet, and two wings, whole like those of a bat, and a snake’s tail.” (Gould, Charles, Mythical Monsters, W.H. Allen & Co., London, 1886, pp. 136-138.) The Italian historian Aldrovandus also claimed to have received in the year 1551 a “true dried Aethiopian dragon” a watercolor of which appears to the right. At first glance, one is tempted agree with Gould that the wings are ridiculously small. But perhaps in transporting from Ethiopia the wings broke off or disintegrated and thus had to be added from the artist’s imagination.

remarkable form. Bellonius states that he had seen whole carcases [sic] of winged dragons, carefully prepared, which he considered to be of the same kind as those which fly out of Arabia into Egypt; they were thick about the belly, had two feet, and two wings, whole like those of a bat, and a snake’s tail.” (Gould, Charles, Mythical Monsters, W.H. Allen & Co., London, 1886, pp. 136-138.) The Italian historian Aldrovandus also claimed to have received in the year 1551 a “true dried Aethiopian dragon” a watercolor of which appears to the right. At first glance, one is tempted agree with Gould that the wings are ridiculously small. But perhaps in transporting from Ethiopia the wings broke off or disintegrated and thus had to be added from the artist’s imagination.

The first century Greek historian Strabo, who traveled and researched extensively throughout the Mediterranean and Near East, wrote a treatise on geography. He explained that in India “there are reptiles two cubits long with membranous wings like bats, and that they too fly by night, discharging drops of urine, or also of sweat, which putrefy the skin of anyone who is not on his guard;” (Strabo, Geography: Book XV: “On India,” Chap. 1, No. 37, AD 17, pp. 97-98.) Strabos account may have been based in part on the earlier work of Megasthenes (ca 350 – 290 BC) who traveled to India and states that there are “snakes (ophies) with wings, and that their visitations occur not during the daytime but by night, and that they emit urine which at once produces a festering wound on any body on which it may happen to drop.” (Aelianus, Greek Natural History:On Animals, 3rd century AD, 16.41.)

The Chinese have many stories of dragons. Some ornamental pictures of dragons are shaped remarkably like dinosaurs. Marco Polo wrote of his travels to the province of Karajan and reported on huge serpents, which at the fore part have two short legs, each with three claws. “The jaws are wide enough to swallow a man, the teeth are large and sharp, and their whole appearance is so formidable that neither man, nor any kind of animal can approach them without terror.” (Polo, Marco, The Travels of Marco Polo, 1961, pp. 158-159.) Books even tell of Chinese families raising dragons to use their blood for medicines and highly prizing their eggs. (DeVisser, Marinus Willem, The Dragon in China & Japan, 1969.) To the top right are pictures of a fossilized dinosaur egg compared to a chicken egg and a Protoceratops dinosaur egg that is double-yoked. It is interesting that the twelve signs of the Chinese zodiac are all animals–eleven of which are still alive today.

The Chinese have many stories of dragons. Some ornamental pictures of dragons are shaped remarkably like dinosaurs. Marco Polo wrote of his travels to the province of Karajan and reported on huge serpents, which at the fore part have two short legs, each with three claws. “The jaws are wide enough to swallow a man, the teeth are large and sharp, and their whole appearance is so formidable that neither man, nor any kind of animal can approach them without terror.” (Polo, Marco, The Travels of Marco Polo, 1961, pp. 158-159.) Books even tell of Chinese families raising dragons to use their blood for medicines and highly prizing their eggs. (DeVisser, Marinus Willem, The Dragon in China & Japan, 1969.) To the top right are pictures of a fossilized dinosaur egg compared to a chicken egg and a Protoceratops dinosaur egg that is double-yoked. It is interesting that the twelve signs of the Chinese zodiac are all animals–eleven of which are still alive today.

But is the twelfth, the dragon merely a legend or is it based on a real animal– the dinosaur? It doesn’t seem logical that the ancient Chinese, when constructing their zodiac, would include one mythical animal with eleven real animals. ”The interpretation of dinosaurs as dragons goes

But is the twelfth, the dragon merely a legend or is it based on a real animal– the dinosaur? It doesn’t seem logical that the ancient Chinese, when constructing their zodiac, would include one mythical animal with eleven real animals. ”The interpretation of dinosaurs as dragons goes

back more than two thousand years in Chinese culture. They were regarded as sacred, as a symbol of power…” (Zhiming, Doug, Dinosaurs From China, 1988, p. 9.) Shown to the left is a dragon that was cast in red gold and embossed during the Tang Dynasty (618-906 AD). Notice the long neck and tail, the frills, and the lithe stance. Shown right is a ferocious Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 AD) dragon statue (click to enlarge) that is part of the Barakat Gallery Collection.

back more than two thousand years in Chinese culture. They were regarded as sacred, as a symbol of power…” (Zhiming, Doug, Dinosaurs From China, 1988, p. 9.) Shown to the left is a dragon that was cast in red gold and embossed during the Tang Dynasty (618-906 AD). Notice the long neck and tail, the frills, and the lithe stance. Shown right is a ferocious Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 AD) dragon statue (click to enlarge) that is part of the Barakat Gallery Collection.

“Among Serpents, we find some that are furnished with Wings. Herodotus who saw those Serpents, says they had great Resemblance to those which the Greeks and Latins call’d Hydra; their Wings are not compos’d of Feathers like the Wings of Birds, but rather like to those of Batts; they love sweet smells, and frequent such Trees as bear Spices. These were the fiery Serpents that made so great a Destruction in the Camp of Israel…The brazen Serpent was a Figure of the flying Serpent, Saraph, which Moses fixed upon an erected Pole: That there were such, is most evident. Herodotus who had seen of those Serpents, says they very much resembled those which the Greeks and Latins called Hydra: He went on purpose to the City of Brutus to see those flying Animals, that had been devour’d by the Ibidian Birds.” (Owen, Charles, An Essay Towards a Natural History of Serpents, 1742, pp. 191-193.)

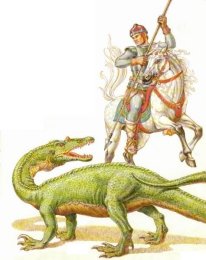

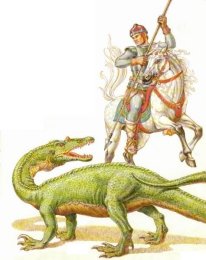

In medieval times, the Scandinavians described swimming dragons and the Vikings placed dragons on the front of their ships to scare off the sea monsters. The one pictured to the right is based upon the 1734 sighting by Hans Egede. As a missionary to Greenland, Egede was known as a meticulous recorder of the natural world. Numerous such stories have been recorded from the age of sailing ships (1500-1900 A.D.). The familiar story of Beowulf and the legend of Saint George slaying a dragon, which are well-known in the annals of English literature, likely have some basis in fact. Indeed the “dragon” pictured to the left is the dinosaur Baryonyx, whose skeleton has been found in England. Dragons were even described in reputable zoological treatises published during the Middle Ages. For example, the great Swiss naturalist and medical doctor Konrad Gesner published a four-volume encyclopedia from 1516-1565 entitled Historiae Animalium. He mentioned dragons as “very rare but still living creatures” (p.224). The story is told of a tenth century Irishman who encountered a large clawed beast having “iron on its tail which pointed backwards.” It had a head similar to a horse. It also had thick legs and strong claws. Could this have been a surviving Stegosaurus? (Ham, K., The Great Dinosaur Mystery Solved, 1999, p.33.)

In medieval times, the Scandinavians described swimming dragons and the Vikings placed dragons on the front of their ships to scare off the sea monsters. The one pictured to the right is based upon the 1734 sighting by Hans Egede. As a missionary to Greenland, Egede was known as a meticulous recorder of the natural world. Numerous such stories have been recorded from the age of sailing ships (1500-1900 A.D.). The familiar story of Beowulf and the legend of Saint George slaying a dragon, which are well-known in the annals of English literature, likely have some basis in fact. Indeed the “dragon” pictured to the left is the dinosaur Baryonyx, whose skeleton has been found in England. Dragons were even described in reputable zoological treatises published during the Middle Ages. For example, the great Swiss naturalist and medical doctor Konrad Gesner published a four-volume encyclopedia from 1516-1565 entitled Historiae Animalium. He mentioned dragons as “very rare but still living creatures” (p.224). The story is told of a tenth century Irishman who encountered a large clawed beast having “iron on its tail which pointed backwards.” It had a head similar to a horse. It also had thick legs and strong claws. Could this have been a surviving Stegosaurus? (Ham, K., The Great Dinosaur Mystery Solved, 1999, p.33.)

Ulysses Aldrovandus is considered by many to be the father of modern natural history. He traveled extensively, collected thousands of animals and plants, and created the first ever natural history museum. His impressive collections are still on display at the Bologna University (the world’s oldest university) where they attest to his scholarship. His credentials give credence to an incident that Aldrovandus personally reported concerning a dragon. The dragon was first seen on May 13, 1572, hissing like a snake. It had been hiding on the small estate of Master Petronius. At 5:00 PM, the dragon was caught on a public roadway by a herdsman named Baptista, near the hedge of a private farm, a mile from the remote city outskirts of Bologna. Baptista was following his ox cart home when he noticed the oxen suddenly come to a stop. He kicked them and shouted at them, but they refused to move and went down on their knees rather than move forward.

Ulysses Aldrovandus is considered by many to be the father of modern natural history. He traveled extensively, collected thousands of animals and plants, and created the first ever natural history museum. His impressive collections are still on display at the Bologna University (the world’s oldest university) where they attest to his scholarship. His credentials give credence to an incident that Aldrovandus personally reported concerning a dragon. The dragon was first seen on May 13, 1572, hissing like a snake. It had been hiding on the small estate of Master Petronius. At 5:00 PM, the dragon was caught on a public roadway by a herdsman named Baptista, near the hedge of a private farm, a mile from the remote city outskirts of Bologna. Baptista was following his ox cart home when he noticed the oxen suddenly come to a stop. He kicked them and shouted at them, but they refused to move and went down on their knees rather than move forward.

At this point, the herdsman noticed a hissing sound and was startled to see this strange little dragon ahead of him.Trembling he struck it on the head with his rod and killed it. (Aldrovandus, Ulysses, The Natural History of Serpents and Dragons, 1640, p.402.) Aldrovandus surmised that dragon was a juvenile, judging by the incompletely developed claws and teeth.The corpse had only two feet and moved both by slithering like a snake and by using its feet, he believed. (There are small two-legged lizards that do this today.) Aldrovandus mounted the specimen and displayed it for some time. He also had a watercolor painting of the creature made (see upper left).

At this point, the herdsman noticed a hissing sound and was startled to see this strange little dragon ahead of him.Trembling he struck it on the head with his rod and killed it. (Aldrovandus, Ulysses, The Natural History of Serpents and Dragons, 1640, p.402.) Aldrovandus surmised that dragon was a juvenile, judging by the incompletely developed claws and teeth.The corpse had only two feet and moved both by slithering like a snake and by using its feet, he believed. (There are small two-legged lizards that do this today.) Aldrovandus mounted the specimen and displayed it for some time. He also had a watercolor painting of the creature made (see upper left).

In Medieval times, scientifically minded authors produced volumes called “bestiaries,” a compilation of known (and sometimes imaginary) animals accompanied by a moralizing explanation and fascinating pictures. One such volume is the Aberdeen Bestiary, written in the early 1500s and preserved in the library of Henry VIII. Along with the newt, the salamander, and various kinds of snakes is the description and depiction of the dragon: “The dragon is bigger than all other snakes or all other living things on earth. For this reason, the Greeks call it dracon, from this is derived its Latin name draco. The dragon, it is said, is often drawn forth from caves into the open air, causing the air to become turbulent. The dragon has a crest, a small mouth, and narrow blow-holes through which it breathes and puts forth its tongue. Its strength lies not in its teeth but in its tail, and it kills with a blow rather than a bite. It is free from poison. They say that it does not need poison to kill things, because it kills anything around which it wraps its tail. From the dragon not even the elephant, with its huge size, is safe. For lurking on paths along which elephants are accustomed to pass, the dragon knots its tail around their legs and kills them by suffocation. Dragons are born in Ethiopia and India, where it is hot all year round.” Flavious Philostratus, the third century historian provided this sober account: “The whole of India is girt with dragons of enormous size; for not only the marshes are full of them, but the mountains as well, and there is not a single ridge without one. Now the marsh kind are sluggish in their habits and are thirty cubits long, and they have no crest standing up on their heads.” (Philostratus, Flavius, The Life of Apollonius of Tyanna, 170 AD.) Pliny the Elder also referenced large dragons in India in his Natural History.

In Medieval times, scientifically minded authors produced volumes called “bestiaries,” a compilation of known (and sometimes imaginary) animals accompanied by a moralizing explanation and fascinating pictures. One such volume is the Aberdeen Bestiary, written in the early 1500s and preserved in the library of Henry VIII. Along with the newt, the salamander, and various kinds of snakes is the description and depiction of the dragon: “The dragon is bigger than all other snakes or all other living things on earth. For this reason, the Greeks call it dracon, from this is derived its Latin name draco. The dragon, it is said, is often drawn forth from caves into the open air, causing the air to become turbulent. The dragon has a crest, a small mouth, and narrow blow-holes through which it breathes and puts forth its tongue. Its strength lies not in its teeth but in its tail, and it kills with a blow rather than a bite. It is free from poison. They say that it does not need poison to kill things, because it kills anything around which it wraps its tail. From the dragon not even the elephant, with its huge size, is safe. For lurking on paths along which elephants are accustomed to pass, the dragon knots its tail around their legs and kills them by suffocation. Dragons are born in Ethiopia and India, where it is hot all year round.” Flavious Philostratus, the third century historian provided this sober account: “The whole of India is girt with dragons of enormous size; for not only the marshes are full of them, but the mountains as well, and there is not a single ridge without one. Now the marsh kind are sluggish in their habits and are thirty cubits long, and they have no crest standing up on their heads.” (Philostratus, Flavius, The Life of Apollonius of Tyanna, 170 AD.) Pliny the Elder also referenced large dragons in India in his Natural History.

The 16th century Italian explorer Pigafetta, in a report of the kingdom of Congo, described the province of Bemba, which he defines as “on the sea coast from the river Ambrize, until the river Coanza towards the south,” and says of serpents, “There are also certain other creatures which, being as big as rams, have wings like dragons, with long tails, and long chaps, and divers rows of teeth, and feed upon raw flesh. Their colour is blue and green, their skin painted like scales, and they have two feet but no more. The Pagan negroes used to worship them as gods, and to this day you may see divers of them that are kept for a marvel. And because they are very rare, the chief lords there curiously preserve them, and suffer the people to worship them, which tendeth greatly to their profits by reason of the gifts and oblations which the people offer unto them.” (Pigafetta, Filippo, The Harleian Collections of Travels, vol. ii, 1745, p. 457.)

Daniel was said to kill a dragon in the apocryphal chapters of the Bible. King Cyrus challenged Daniel’s refusal to worship the idol Bel. Daniel revealed to the king a conspiracy on the part of the priests to eat the food offered to Bel, making the god seem real. Not only were the deceptive priests executed, but Daniel was allowed to destroy their idol and a dragon that was being worshipped. In the brief narrative of the dragon (14:23-30), Daniel killed the dragon by baking pitch, fat, and hair to make cakes that cause the dragon to burst open upon consumption. In the Hebrew Midrash version, other ingredients serve the purpose of destroying the dragon.

After Alexander the Great invaded India he brought back reports of seeing a great hissing dragon living in a cave. Later Greek rulers supposedly brought dragons alive from Ethiopia. (Gould, Charles, Mythical Monsters, W.H. Allen & Co., London, 1886, pp. 382-383.) Microsoft Encarta Encyclopedia (“Dinosaur” entry) explains that the historical references to dinosaur bones may extend as far back as the 5th century BC. In fact, some scholars think that the Greek historian Herodotus was referring to fossilized dinosaur skeletons and eggs when he described griffins guarding nests in central Asia. “Dragon bones” mentioned in a 3rd century AD text from China are thought to refer to bones of dinosaurs.

Ancient explorers and historians, like Josephus, told of small flying reptiles in ancient Egypt and Arabia and described their predators, the ibis, stopping their invasion into Egypt. (Epstei+n, Perle S., Monsters: Their Histories, Homes, and Habits, 1973, p.43.) A third century historian Gaius Solinus, discussed the Arabian flying serpents, and stated that “the poison is so quick that death follows before pain can be felt.” (Cobbin, Ingram, Condensed Commentary and Family Exposition on the Whole Bible, 1837, p. 171.) The well-respected Greek researcher Herodotus wrote: “There is a place in Arabia, situated very near the city of Buto, to which I went, on hearing of some winged serpents; and when I arrived there, I saw bones and spines of serpents, in such quantities as it would be impossible to describe. The form of the serpent is like that of the water-snake; but he has wings without feathers, and as like as possible to the wings of a bat.” (Herodotus, Historiae, tr. Henry Clay, 1850, pp. 75-76.) Herodotus has been called “the Father of History” because he was the first historian we know who collected his materials systematically and then tested them for accuracy. John Goertzen noted the Egyptian representation of tail vanes with flying reptiles and concluded that they must have observed pterosaurs or they would not have known to sketch this leaf-shaped tail. He also matched a flying reptile, observed in Egypt and sketched by the outstanding Renaissance scientist Pierre Belon, with the Dimorphodon genus of pterosaur. (Goertzen, J.C., “Shadows of Rhamphorhynchoid Pterosaurs in Ancient Egypt and Nubia,” Cryptozoology, Vol 13, 1998.)

Charles Gould cites the historian Gesner as saying that, “In 1543, a kind of dragon appeared near Styria, within the confines of Germany, which had feet like lizards, and wings after the fashion of a bat, with an incurable bite… He refers to a description by Scaliger (Scaliger, lib. III. Miscellaneous cap. i, “Winged Serpents,” p. 182.) of a species of serpent four feet long, and as thick as a man’s arm, with cartilaginous wings pendent from the sides. He also mentions Brodeus, of a winged dragon which was brought to Francis, the invincible King of the Gauls, by a countryman who had killed it with a mattock near Sanctones, and which was stated to have been seen by many men of approved reputation, who though it had migrated from transmarine regions by the assistance of the wind. Cardan (De Natura Rerum, lib VII, cap. 29.) states that whilst he resided in Paris he saw five winged dragons in the WilliamMuseum; these were biped, and possessed of wings so slender that it was hardly possible that they could fly with them. Cardan doubted their having been fabricated, since they had been sent in vessels at different times, and yet all presented the same

The first century Greek historian Strabo, who traveled and researched extensively throughout the Mediterranean and Near East, wrote a treatise on geography. He explained that in India “there are reptiles two cubits long with membranous wings like bats, and that they too fly by night, discharging drops of urine, or also of sweat, which putrefy the skin of anyone who is not on his guard;” (Strabo, Geography: Book XV: “On India,” Chap. 1, No. 37, AD 17, pp. 97-98.) Strabos account may have been based in part on the earlier work of Megasthenes (ca 350 – 290 BC) who traveled to India and states that there are “snakes (ophies) with wings, and that their visitations occur not during the daytime but by night, and that they emit urine which at once produces a festering wound on any body on which it may happen to drop.” (Aelianus, Greek Natural History:On Animals, 3rd century AD, 16.41.)

“Among Serpents, we find some that are furnished with Wings. Herodotus who saw those Serpents, says they had great Resemblance to those which the Greeks and Latins call’d Hydra; their Wings are not compos’d of Feathers like the Wings of Birds, but rather like to those of Batts; they love sweet smells, and frequent such Trees as bear Spices. These were the fiery Serpents that made so great a Destruction in the Camp of Israel…The brazen Serpent was a Figure of the flying Serpent, Saraph, which Moses fixed upon an erected Pole: That there were such, is most evident. Herodotus who had seen of those Serpents, says they very much resembled those which the Greeks and Latins called Hydra: He went on purpose to the City of Brutus to see those flying Animals, that had been devour’d by the Ibidian Birds.” (Owen, Charles, An Essay Towards a Natural History of Serpents, 1742, pp. 191-193.)

The 16th century Italian explorer Pigafetta, in a report of the kingdom of Congo, described the province of Bemba, which he defines as “on the sea coast from the river Ambrize, until the river Coanza towards the south,” and says of serpents, “There are also certain other creatures which, being as big as rams, have wings like dragons, with long tails, and long chaps, and divers rows of teeth, and feed upon raw flesh. Their colour is blue and green, their skin painted like scales, and they have two feet but no more. The Pagan negroes used to worship them as gods, and to this day you may see divers of them that are kept for a marvel. And because they are very rare, the chief lords there curiously preserve them, and suffer the people to worship them, which tendeth greatly to their profits by reason of the gifts and oblations which the people offer unto them.” (Pigafetta, Filippo, The Harleian Collections of Travels, vol. ii, 1745, p. 457.)