Geocentrism

- Thread starter zone

- Start date

-

Christian Chat is a moderated online Christian community allowing Christians around the world to fellowship with each other in real time chat via webcam, voice, and text, with the Christian Chat app. You can also start or participate in a Bible-based discussion here in the Christian Chat Forums, where members can also share with each other their own videos, pictures, or favorite Christian music.

If you are a Christian and need encouragement and fellowship, we're here for you! If you are not a Christian but interested in knowing more about Jesus our Lord, you're also welcome! Want to know what the Bible says, and how you can apply it to your life? Join us!

To make new Christian friends now around the world, click here to join Christian Chat.

Too long, did not read. Be more concise.

"I do not feel obliged to believe that the same god who has endowed us with sense, reason, and intellect has intended us to forgo their use and by some other means to give us knowledge which we can attain by them".

-Galileo

here's a summary by another who can't understand what he reads (more probably didn't read it either)

Apparently its still 800 AD and the sun revolves around the earth...

Last edited:

Apparently its still 800 AD and the sun revolves around the earth...

take pieces of paper with you, and make little dots over the course of 6 hours pinpointing where the stars (lights) are in relation to you.

do it again the next night.

then come back and tell me you are on a planet hurtling through space, while that planet is spinning.

do you understand the concept?

think of it as a game.

okay?

don't have issues with the time thing. God could have sped things up whenever He wanted to.

hmm the multiquote option didn't work as well as hoped.

anyway I check them out but I highly doubt it will change my mind about a tilted Earth that rotates (causes day and night) and revolves around the sun (causing the seasons) which in turn rotates around the galaxy center.

I am still not convinced that GOD tells men in the Bible that the Earth is the center of the universe.

It sounds like a manmade tradition to me.

yes the Jewish people might have believed it but they have been wrong about what God meant in Scripture before.

hmm the multiquote option didn't work as well as hoped.

anyway I check them out but I highly doubt it will change my mind about a tilted Earth that rotates (causes day and night) and revolves around the sun (causing the seasons) which in turn rotates around the galaxy center.

I am still not convinced that GOD tells men in the Bible that the Earth is the center of the universe.

It sounds like a manmade tradition to me.

yes the Jewish people might have believed it but they have been wrong about what God meant in Scripture before.

is evolution true?

A

can you find me any?

Parallax

i like this video:

Stellar Parallax Interactive

you have to click on the stellar parallax interactive...

they say Friedrich Bessel first observed Parallax on the star 61 Cygn,

he also first noted the concept of refraction of light by the Earth's atmosphere.

Friedrich Bessel and the Companion of Sirius

Last edited by a moderator:

"One can of course believe anything one likes as long as the consequences of that belief are trivial. But when survival depends on belief, then it matters that belief corresponds to manifest reality.

We therefore teach navigators that the stars are fixed to the Celestial Sphere, which is centered on a fixed Earth, and around which it rotates in accordance with laws clearly deducible from common-sense observation.

The Sun and Moon move across the inner surface of this sphere, and hence perforce go around the Earth.

This means that students of navigation must unlearn a lot of the confused dogma they learned in school. Most of them find this remarkably easy, because dogma is as may be, but the real world is as we perceive it to be.

If Andrew Hill will look in the Journal of Navigation he will find that the Earth-centered Universe is alive and well, whatever his readings of the Spectator may suggest."

Darcy Peddyhoff

Royal Air Force College

Cranwell

Lincolnshire, England

'New Scientist', Aug. 16, 1979, p. 543

We therefore teach navigators that the stars are fixed to the Celestial Sphere, which is centered on a fixed Earth, and around which it rotates in accordance with laws clearly deducible from common-sense observation.

The Sun and Moon move across the inner surface of this sphere, and hence perforce go around the Earth.

This means that students of navigation must unlearn a lot of the confused dogma they learned in school. Most of them find this remarkably easy, because dogma is as may be, but the real world is as we perceive it to be.

If Andrew Hill will look in the Journal of Navigation he will find that the Earth-centered Universe is alive and well, whatever his readings of the Spectator may suggest."

Darcy Peddyhoff

Royal Air Force College

Cranwell

Lincolnshire, England

'New Scientist', Aug. 16, 1979, p. 543

Genesis 1

The Creation

1In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.2The earth was formless and void, and darkness was over the surface of the deep, and the Spirit of God was moving over the surface of the waters.3Then God said, “Let there be light”; and there was light.4God saw that the light was good; and God separated the light from the darkness.5God called the light day, and the darkness He called night. And there was evening and there was morning, one day.

6Then God said, “Let there be an expanse in the midst of the waters, and let it separate the waters from the waters.”7God made the expanse, and separated the waters which were below the expanse from the waters which were above the expanse; and it was so.8God called the expanse heaven. And there was evening and there was morning, a second day.

9Then God said, “Let the waters below the heavens be gathered into one place, and let the dry land appear”; and it was so.10God called the dry land earth, and the gathering of the waters He called seas; and God saw that it was good.11Then God said, “Let the earth sprout vegetation, plants yielding seed, and fruit trees on the earth bearing fruit after their kind with seed in them”; and it was so.12The earth brought forth vegetation, plants yielding seed after their kind, and trees bearing fruit with seed in them, after their kind; and God saw that it was good.13There was evening and there was morning, a third day.

14Then God said, “Let there be lights in the expanse of the heavens to separate the day from the night, and let them be for signs and for seasons and for days and years;15and let them be for lights in the expanse of the heavens to give light on the earth”; and it was so.16God made the two great lights, the greater light to govern the day, and the lesser light to govern the night; He made the stars also.17God placed them in the expanse of the heavens to give light on the earth,18and to govern the day and the night, and to separate the light from the darkness; and God saw that it was good.19There was evening and there was morning, a fourth day.

The Creation

1In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.2The earth was formless and void, and darkness was over the surface of the deep, and the Spirit of God was moving over the surface of the waters.3Then God said, “Let there be light”; and there was light.4God saw that the light was good; and God separated the light from the darkness.5God called the light day, and the darkness He called night. And there was evening and there was morning, one day.

6Then God said, “Let there be an expanse in the midst of the waters, and let it separate the waters from the waters.”7God made the expanse, and separated the waters which were below the expanse from the waters which were above the expanse; and it was so.8God called the expanse heaven. And there was evening and there was morning, a second day.

9Then God said, “Let the waters below the heavens be gathered into one place, and let the dry land appear”; and it was so.10God called the dry land earth, and the gathering of the waters He called seas; and God saw that it was good.11Then God said, “Let the earth sprout vegetation, plants yielding seed, and fruit trees on the earth bearing fruit after their kind with seed in them”; and it was so.12The earth brought forth vegetation, plants yielding seed after their kind, and trees bearing fruit with seed in them, after their kind; and God saw that it was good.13There was evening and there was morning, a third day.

14Then God said, “Let there be lights in the expanse of the heavens to separate the day from the night, and let them be for signs and for seasons and for days and years;15and let them be for lights in the expanse of the heavens to give light on the earth”; and it was so.16God made the two great lights, the greater light to govern the day, and the lesser light to govern the night; He made the stars also.17God placed them in the expanse of the heavens to give light on the earth,18and to govern the day and the night, and to separate the light from the darkness; and God saw that it was good.19There was evening and there was morning, a fourth day.

......

why does NASA predict Lunar and Solar eclipses and the positioning of all other planets according to the Geocentric model?

NASA - 12-Year Ephemeris < click

why does NASA predict Lunar and Solar eclipses and the positioning of all other planets according to the Geocentric model?

NASA - 12-Year Ephemeris < click

K

The problem is, that mathematically, distances to the stars does not enter into observing crossing, as it does into visibility of parallax. Only the relative distance of the two crossing stars is needed. Stars cross (if they do) because one is twice as far as the other from the earth, and they lie in line with the center of the earth's orbit. From winter to summer, two stars in line with the sun and earth's position at spring, but one farther out from the other, would make the closer one appear to shift from the right side of the farther to the left side. With all the stars out there, it is unthinkable that this configuration never happens.

Unless stars are observed to cross, all the observable parallax data can be explained by an alternate theory that they are all painted or hung on hooks, on some solid firmament millions of miles out, and observed parallax can just as easily be the annual movement of stars around a little wheel of their own, fixed to rotate once a year. The relative size of the wheels then makes us think the stars with smaller wheels are farther out. That is what the ancients said the planets were, so we cannot dispense with this alternate theory.

A

people, primarily academics believed (?) and taught, and still believe (?) and teach evolution.

is evolution true?

is evolution true?

For example that mutations produce favorable traits.

I believe God created the genome of each living creature to already have the traits they needed to survive and adapt but not all genes are expressed.

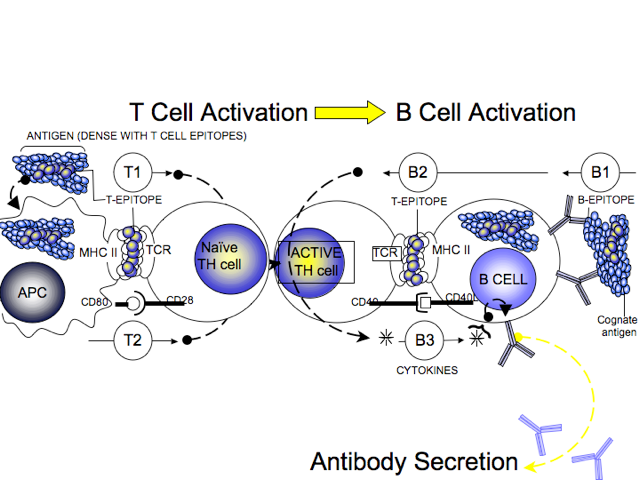

My microbiology teacher told me that our Beta cells had within them all the CD4 T cells coded for specific peptides found in every virus or bacteria known on the planet even before we encountered them.

I think that was the quote...mmm should look at my notes....

Personally I'm constantly amazed at how complex and detailed God has made His creations.

He gave us the ability to heal and so many take that for granted until their body no longer operates as it should.

B-cell activation by armed helper T cells - Immunobiology - NCBI Bookshelf

"a CD4 T cell specific for peptides from this pathogen must first be activated to produce the appropriate armed helper T cells"

One of the most puzzling features of the antibody response is how an antigenspecific B cell manages to encounter a helper T cell with an appropriate antigen specificity. This question arises because the frequency of naive lymphocytes specific for any given antigen is estimated to be between 1 in 10,000 and 1 in 1,000,000. Thus, the chance of an encounter between a T lymphocyte and a B lymphocyte that recognize the same antigen should be between 1 in 10[SUP]8[/SUP] and 1 in 10[SUP]12[/SUP]. Achieving such an encounter is a far more difficult challenge than getting effector T cells activated, because, in the latter case, only one of the two cells involved has specific receptors. Moreover, T cells and B cells mostly occupy quite distinct zones in peripheral lymphoid tissue (see Fig. 1.8). As in naive T-cell activation (see Chapter 8), the answer seems to lie in the antigen-specific trapping of migrating lymphocytes.

When an antigen is introduced into an animal, it is captured and processed by professional antigen-presenting cells, especially the dendritic cells that migrate from the tissues into the T-cell zones of local lymph nodes. Recirculating naive T cells pass by such cells continuously and those rare T cells whose receptors bind peptides derived from the antigen are trapped very efficiently. This trapping clearly involves the specific antigen receptor on the T cell,

When an antigen is introduced into an animal, it is captured and processed by professional antigen-presenting cells, especially the dendritic cells that migrate from the tissues into the T-cell zones of local lymph nodes. Recirculating naive T cells pass by such cells continuously and those rare T cells whose receptors bind peptides derived from the antigen are trapped very efficiently. This trapping clearly involves the specific antigen receptor on the T cell,

"a helper T cell with an appropriate antigen specificity." is in our lymph nodes even before we ever get sick.

J

THERE IS NO EASY EXPLANATION FOR THIS JUST EASY ANSWERS. THE MOST RECENT SUPPORT FOR EVOLUTION CONCERNS THE RH (RHESUS MONKEY) FACTOR IN HUMAN BLOOD AND THE LACK THEREOF.IF YOUR BOOD FACTOR IS POSITIVE THAT MEANS IT CONTAINS THE RHESUS MONKEY GENE. WE COULD NOT HAVE EVOLVED FROM THE RHESUS MONKEY HOWEVER BECAUSE IF WE HAD WE WOULD BE THE RHESUS MONKEY AND THEY WOULD NO LONGER EXIST. THEY WOULD ESSENTIALLY HAVE TO BE THEORIZED AS HAVING ONCE EXISTED AS THE REASON FOR THE POSITIVE RESULT. THEN AGAIN IF YOU TEST NEGATIVE FOR THE RHESUS MONKEY GENE IT TENDS TO DEBUNK EVOLUTION ENTIRELY AND SO SCIENTISTS HAVE DECLARED THAT THIS IS AN ALIEN FACTOR WHICH DOES NOT COME FROM EARTH BECAUSE IT DIDN'T EVOLVE FROM MONKEYS. THE MORE LIKELY EXPLANATION WOULD BE THAT THE NEGATIVE FACTOR BLOOD IS HUMAN BLOOD AND THE RHESUS MONKEY FACTOR BLOOD HAS BEEN GENETICALLY TAMPERED WITH THROUGH WELL KNOWN NAZI EXPERIMENTS AND THOSE OF OTHER SCIENTISTS WHO WOULD OF COURSE COVER THEIR TRACKS IF THEY WERE GUILTY OF SUCH A CRIME. ALL HYPOTHETICAL ON BOTH SIDES OF COURSE AND I HAVEN'T ACTUALLY SEEN MY ARGUMENT ANYWHERE.....THEORETICAL THINKING CANNOT BE THE BASIS FOR FACTUAL THINKING IN ANY EVENT. BEST EVIDENCE IS ON THE SIDE OF CREATION ESP WITH THE NEWER KNOWLEDGE OF DNA WHICH HAS BEEN SHOWTO BE A HIGHLY SOPHISTICATED ENCRYPTED LANGUAGE. EVEN IF YOU COULD DETERMINE THAT WE WERE GENETICALLY ENGINEERED BY ALIEN BEINGS AS THEY WOULD HAVE YOU TO BELIEVE THE QUESTION STILL REMAINS AS TO WHERE THOSE BEINGS CAME FROM ETC ETC BACK THROUGH THE REACHES OF TIME

SO.....MY BEST ADVICE IS FOR YOU TO PRAY ABOUT IT AND SEE WHERE THAT LEADS YOU. IF YOU GIVE GOD EVEN HALF A CHANCE HE WILL PROVE HIMSELF EVERY TIME

SO.....MY BEST ADVICE IS FOR YOU TO PRAY ABOUT IT AND SEE WHERE THAT LEADS YOU. IF YOU GIVE GOD EVEN HALF A CHANCE HE WILL PROVE HIMSELF EVERY TIME

......

why does NASA predict Lunar and Solar eclipses and the positioning of all other planets according to the Geocentric model?

NASA - 12-Year Ephemeris < click

why does NASA predict Lunar and Solar eclipses and the positioning of all other planets according to the Geocentric model?

NASA - 12-Year Ephemeris < click

Astronomy Picture of the Day

Discover the cosmos! Each day a different image or photograph of our fascinating universe is featured, along with a brief explanation written by a professional astronomer.

2007 June 21

Stars and the Solstice Sun

Explanation: If you could turn off the atmosphere's ability to scatter overwhelming sunlight, today's daytime sky might look something like this ... with the Sun surrounded by the stars of the constellations Taurus and Gemini. Of course, today is the Solstice. Traveling along the ecliptic plane, the Sun is at its northernmost position in planet Earth's sky, marking the astronomical beginning of summer in the north. Accurate for the exact time of today's Solstice, this composite image also shows the Sun at the proper scale (about the angular size of the Full Moon). Open star cluster M35 is to the Sun's left, and the other two bright stars in view are Mu and Eta Geminorum. Digitally superimposed on a nighttime image of the stars, the Sun itself is a composite of a picture taken through a solar filter and a series of images of the solar corona recorded during the solar eclipse of February 26, 1998 by Andreas Gada.

APOD: 2007 June 21 - Stars and the Solstice Sun < click

can anyone tell me if NASA is using a Geocentric model here?

A

......

why does NASA predict Lunar and Solar eclipses and the positioning of all other planets according to the Geocentric model?

NASA - 12-Year Ephemeris < click

why does NASA predict Lunar and Solar eclipses and the positioning of all other planets according to the Geocentric model?

NASA - 12-Year Ephemeris < click

"An ephemeris is a table of values that gives the positions of astronomical objects in the sky over a range of times, while geocentric means "as seen from Earth's center.""

therefore "geocentric ephemeris" is not supporting a geocentric model of the universe, but just a table of values of where astronomical objects in the sky are located in respect to an observer on the Earth.

BEST EVIDENCE IS ON THE SIDE OF CREATION ESP WITH THE NEWER KNOWLEDGE OF DNA WHICH HAS BEEN SHOWTO BE A HIGHLY SOPHISTICATED ENCRYPTED LANGUAGE.

that highly encrypted language (DNA) is information.

evolution says (with whatever amino acid or alien life matter coincidentally hitting earth tweaking you mix in later, when your [you evolutionists] stupid theory is proven bogus):

TIME + ENERGY (sun beating down for billions of years) + DEAD MATTER (a rock?) = LIFE.

evolution's theory is missing the vital component of INFORMATION.

no life can exist without information as a component.

infinity of the sun beating down on lifeless matter will never spontaneously create life.

for a theory to ever be more than a theory it must be repeatable.

A

can anyone tell me if NASA is using a Geocentric model here?

You already know that the word "gospel" means a lot of different things to different people.

I think you are misunderstanding the terms...

"An ephemeris is a table of values that gives the positions of astronomical objects in the sky over a range of times, while geocentric means "as seen from Earth's center.""

therefore "geocentric ephemeris" is not supporting a geocentric model of the universe, but just a table of values of where astronomical objects in the sky are located in respect to an observer on the Earth.

"An ephemeris is a table of values that gives the positions of astronomical objects in the sky over a range of times, while geocentric means "as seen from Earth's center.""

therefore "geocentric ephemeris" is not supporting a geocentric model of the universe, but just a table of values of where astronomical objects in the sky are located in respect to an observer on the Earth.

if you are not an observer on the earth, you have only a theory.

please see the following very cool interactive program.

i'll give instructions so you can see how the Geocentric model actually works, by using the model you think is true.

A

t.y.

that highly encrypted language (DNA) is information.

evolution says (with whatever amino acid or alien life matter coincidentally hitting earth tweaking you mix in later, when your [you evolutionists] stupid theory is proven bogus):

TIME + ENERGY (sun beating down for billions of years) + DEAD MATTER (a rock?) = LIFE.

that highly encrypted language (DNA) is information.

evolution says (with whatever amino acid or alien life matter coincidentally hitting earth tweaking you mix in later, when your [you evolutionists] stupid theory is proven bogus):

TIME + ENERGY (sun beating down for billions of years) + DEAD MATTER (a rock?) = LIFE.

evolution's theory is missing the vital component of INFORMATION.

no life can exists without information as a component.

infinity of the sun beating down on lifeless matter will never spontaneously create life.

for a theory to ever be more than a theory it must be repeatable.

no life can exists without information as a component.

infinity of the sun beating down on lifeless matter will never spontaneously create life.

for a theory to ever be more than a theory it must be repeatable.

the theory evolution assumes that a population of a species already exists and then explains how that species changes over time.

the basic concepts really doesn't go against the Bible.

its when people start adding their speculation such as the Big bang theory or abiogenesis that it starts to get shift into lies and teachings that are contrary to the Bible.

For example the idea of natural selection:

the moths. before the industrial revolution the trees were white so more white moves survived in the population but there were still a few grayish ones.

after the factories poluted the area and turned the tree bark darker, more of the darker moths survived because they were better able to camoflauge.

then after the air cleared up and the trees returned to their paler color more white moths were seen in comparison to gray.

that is an example of natural selections: individuals of a population with traits best suited to the environment will survive.

like i said before God already gave that population/ species the different range of traits, it just depended upon the environment to which genetic variation was expressed.

so this aspect of evolutionary theory makes sense and does not contradict anything God has revealed in the Bible.